Whistlepunks and Geoducks

Ron Strickland

With a new introduction by William Kittredge.

Dusting off his tape recorder for this companion volume to his popular River Pigs and Cayuses, Ron Strickland focuses on Washington, his adopted home. In Whistlepunks and Geoducks, Strickland introduces readers to a remarkable group of storytellers, from old-timers to new arrivals.

In searching for people whose stories would add up to a portrait of the Evergreen State, Strickland discovered a region as alive with folklore as it is with natural beauty. Ranchers and wheat farmers, fishers and loggers, Indians and city folk, saloonkeepers and Prohibition agents, oystermen and hippies, and, naturally, whistlepunks and geoduck hunters all rub elbows on the streets and trails of Strickland's Washington state. The author provides a helpful glossary to local terms and adds an index to names, places and livelihoods. Black and white photographs from both personal and archive collections allow the reader to see as well as hear the storytellers.

In his introduction, William Kittredge notes that part of the joy of listening to these spirited oral histories lies in experiencing the subject's use of work-place lingo. The pickaroon, for example, is a pike pole used to break up log jams, while the long two-person saws are caller misery whips or Swedish fiddles. "We hunger for stories about specific worlds, and the particularities of making a go of things," Kittredge writes. "We search them for clues about how we might make our own efforts succeed."

About the author

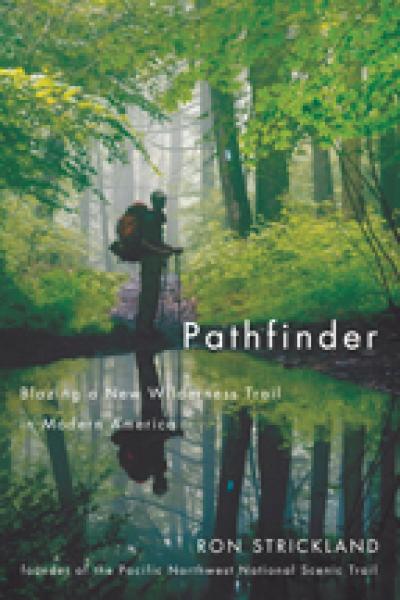

Ron Strickland is the founder of the Pacific Northwest Trail, which stretches 1,200 miles from Glacier National Park in Montana to Washington's Olympic National Park. His books include The Pacific Northwest Trail Guide published by Sasquatch Books, Shanks Mare: A Compendium of Remarkable Walks, and oral histories of Texas, Vermont and Alaska. He lives in Seattle, Washington.

Read more about this author

Listening: Introduction to the New Edition

William Kittredge

Introduction

Ron Strickland

An Indian Woman Scorns a Chief

Isabelle Arcasa

Teamster

Dave Beck

Chief of the Tarheels

Frank "Bow Hill" Bob

4-H Horse Lover

Laura Borders

Captain, "Lady of the Lake"

Earl Bryant

Building with Logs

South Burn

Legendary Boy Scouts Leader

Ome Daiber

"We Lived by the Tides"

Etta Leightheart Egeland

Civic Leader

Jim Ellis

Log Roller

Diane Ellison

Tarheel

Belle Garland

Bush Pilot

Ernie Gibson

Bagging Bucks & Bucking Cords

Konrad Hartbauer

Hobo Railroader

Monte Holm

The Education of a Fighter

Bill Hottell

The View from a Stump Ranch

Walter Jackson

Customs Border Patrol

Harold "Ole" Johnson

"Back There Sucking the Hind Tit"

Dwelley Jones

Willapa Harbor Huck Finn

Joe Krupa

Logger Poet

Judge John Langenbach

Small Ranchers, Working Out

Dave & Marge Leslie

Coal Miner

Ed Marroy

"We Ask Grandfather to Clean Our Minds

Ed "Dutch" Monaghan

Olympic Mountains Outfitter

Minnie Peterson

1962 World's Fair Indian Village Hostess

Helen Peterson

Fourteen-year-old Runaway

Gordon "The Horse Heaven Kid" Poston

College Graduate

Ellen Rainey

Nightriders versus Claimjumpers

Neva Howard Roberts

Horse Packer

Babe Russell

Whisltepunk

Roy "Punk" Shetler

Romanian Immigrant to the Inland Empire

Dr. Israel Soss

Boeing Assembly Line Worker

Adeline "Tiny" Stefano Struble

Geoduck Hunter

Bill Sullivan

Mucker/Mayor

Dennis Sullivan

Icelandic Waterman

Laugi Thorstenson

From Internment Camp to Camping Out

George Uchida

Cascara Brak Peeler

Everett Whealdon

Bear Dancer & Steam Locomotive Fireman

Adulph "Big Dobby" Wiegardt

Highrigger

Hod Wood

Fluming Logs to the Columbia River

Phoebe Yeo

Glossary

This book is a sequel to River Pigs and Cayuses.- Oral Histories from the Pacific Northwest, a collection of interviews I completed in 1979. River Pigs portrayed the region through first-person narratives by rural old-timers, who talked about their experiences as log drive river runners (river pigs), wranglers of wild horses (cayuses), and many other folksy, nostalgic occupations. I believed then that River Pigs was the most evocative portrait I could ever paint of my Pacific Northwest. The experiences of its ranchers, prospectors, blacksmiths, fishermen, gamblers, cowboys, and others were the region for me. I had done it. I had told that story, crossed its t's and dotted its i's.

Well, not quite. I soon wrote Pacific Northwest Trail Guide, a guidebook to a foot-and-horse trail my friends and I had pioneered between the Rockies and the Pacific. In 1983 I hiked that trail's eleven hundred miles.

Clearly I had a tiger by the tail. Certainly there were many more great stories out there if only I would seek them out.

During most of the 1980s I was busy writing and publishing oral histories about other regions of the United States. The experience I gained in writing those books made me realize that I had some unfinished business in my own delightful region. I had to return to finish the story begun in River Pigs and Cayuses. The 1989 Washington state centennial provided the justification for Whistlepunks and Geoducks.

I decided on an extensive tour of Washington similar to ones I had made in Texas and California. My goal was to find people whose stories and experiences would add up to a portrait of the Evergreen state.

If you are a Washingtonian, you may feel slighted because I have not included your favorite story, place, or person. I can only invite you to find and record your own Washingtonians to fill in the gaps I have left.

If you are a newcomer to Washington, I hope that you will be caught up in the thrill of discovery as I was so long ago and happily still am. As an Easterner I love the differences that make my adopted state unique. In northeastern Washington I have encountered the custom whereby a bride and groom's friends will play tricks on them and make a huge hullabaloo after the wedding. On the Strait of Juan de Fuca I have hunted the gargantuan clams called geoducks. In the Methow I have heard old-timers conversing in Chinook, our once universal lingua franca. Everywhere I have revelled in the pleasure of studying local flora and fauna. Take pine trees, for instance. I like the humble lodgepole, especially for its name, so reminiscent of the tree's use in building tepees (which themselves have provided me with fine adventures among the Hill People). A stand of ponderosa pines cries out to me of openness and freedom. Just thinking of whitebark pines transports me to the alpine delights of windswept ridges and distant views.

Washington at its best has always meant Nature to me. And I believe that most ordinary Washingtonians are more Nature-oriented than the citizens of places less blessed by natural beauty.

Only a short time ago the human population was still secondary here to the fish, oysters, deer, elk, bear, and fowl. Even today sea lions routinely gormandize on salmon at Seattle's Ballard locks fish ladder. And just a couple of years ago a cougar was found living in Seattle's Discovery Park.

Love of Nature is such a strong part of our character that I want to share with you a Home Valley, Washington story told to me by ninety-one-year-old Phoebe Yeo.

In 1907 the family by the name of Hadley that lived at Collins got a big Newfoundland dog. We had never seen a Newfoundland and we wanted to pet it.

One day we happened to see the Newfoundland on the road as we were walking the two miles home from school. Well, that silly thing led us right down the road and to the trail that led on up to the woods. We followed it and it would let us get just so close to it. Then it would turn and trot on away from us. It had a long, long tail.

We got tired of following the silly thing. We told it to go on and we'd continue on our way home.

We did not know that that Newfoundland dog was a cougar because we had never seen a mountain lion or a Newfoundland before.

My mother went out to the root cellar to get something for dinner that night. When she was coming back, the cougar went across the field in front of our house after following us children home. Mama knew what it was. So she kept us inside the house.

The mailman, Mr Sholin, carried the mail on foot. Up beyond our house and beyond Collins, where the schoolhouse was later there was an old pine tree. There was a saloon there at that time run by a man named George Raymond. He and his wife raised those nasty pit bulls. I hate those dogs! The pit bulls were out in this field barking up this tree. They had fifteen of them and they were all out there beneath this tree. Mr Sholin saw it was a cougar. The dogs had treed it.

He went to the saloon a short ways away and told Mr. Raymond that his dogs had treed a cougar and that he should take his rifle out there and shoot it.

So that's what Mr Raymond did. He put twelve shots into that animal before it fell out of that tree.

It measured nine feet in length. He skinned it out real carefully and had it mounted into a rug which practically covered their living room floor

Cougars mate for life, and every year after that the mate would come and scream around, hunting for her mate.

Every day my two older sisters, my brother Bruce and I, and our dog Queen would walk two miles up to Porter's mill to school. We'd see that animal. We knew what it was then. But it never bothered us and Queen was with us anyway

We'd see it when we went by. It would be down in a gully lying on a log. It would look up at us and wag and thump its tail and we'd just go on to school and never pay any attention to it. I am sure that it never meant any harm to us children because it had ample time to have killed us all. She was so friendly, making little purring noises and wagging that long tail.

We were never afraid of her. But, do you know, people hunted that thing!

They never got it. When they didn't have a gun, they would see it. And when they hunted it, they'd never see it.

I didn't want them to catch it. I wanted it to go free.

My Washington is a bit like that cougar. I want it to go free. The Washington which I first experienced in 1968 has been slipping inexorably away. The Washington I have known in several decades of rural roaming has changed, developed, and changed some more.

I am not advocating a static society or a declining economy, Revitalization and progress are necessary. But our special Northwest heritage should be appreciated and cherished like that cougar.

Some changes, of course, have been for the better. I am thinking of the improved status of women and minorities in Washington. But consider the following lament from Isabelle Arcasa (born 1889), who complained that at Fourth of July bucking horse contests, "They never had ladies ride or I would have got into it." I asked her about women's liberation. "I think it's great," she said. "If I was young, I'd probably be in amongst them. Couldn't even ride a broomstick now though."

I know that you will enjoy Isabelle Arcasa's story of her parents' marriage. Her mother was a pre-pioneer, an Entiat band Indian, her father a soldier-immigrant from the Middle West. How I wish that I could have talked with them!

However, the richness of Washington folklife has been greatly blessed for me with both Native Americans and genuine pioneers. I wish I could introduce you to prospector Felix Lasota. Eight decades ago, Felix Lasota had tramped through, looking for pay dirt.

When I came in 1903, there was only one cabin in Metaline Falls. There was nothing but a blazed trail between lone and Metaline Falls.

This was a gold mine strike on this (Pend Oreille) River here. They had less than a dozen cabins and one little store across river over at Metaline.

And there were prospectors all down the Pend Oreille River placer mining. At one time there were over fifty Chinamen here working the river too.

There was nothing in Metaline Falls until 1910 when the railroad came in.

My emphasis in River Pigs and Cayuses was on such old-timers. But as one of them, Deke Smith, told me recently, " Dying is just the natural course of Nature. You're born to die. Oh, I feel sad about young people going. Me, I'm just fading out. Like a rock rolling down the hill, he don't roll fast at first. Then he speeds up. I'm rolling faster now than I would like."

My interviewing has evolved in the last decade to be representative of today as well as yesterday. After all, as people like Deke Smith round their "last switchback," I don't want to work myself out of a wonderful job.

And what is my job, you ask? Besides choosing interesting people who are relevant to the regional portrait I am trying to paint, my art as a folklorist is to bring out the best in someone. The best stories. The most honest and/or deeply felt recollections. Such interviews are difficult, not only because the subject is likely to be foreign to the interviewer, but also because the goal of the hunt may not be known at the beginning of the chase.

Beyond that, the question arises of how authentic the edited version is compared to what an interviewee actually said into the microphone. My approach is to edit a person's speech very carefully to retain his actual words and characteristic expressions, but to make the story flow smoothly as a first-person account. I then test the edited version on the interviewee I become in effect a ghostwriter of short autobiographies.

I have always thought that the possibilities of this format are particularly appropriate for a state such as Washington where people are so divided by vast gulfs of distance and culture. How many of us have had the opportunity to meet a salmon-smoking Makah from Neah Bay, or a gold miner from Ferry County, or a wheat rancher from Walla Walla? Do they speak the stereotypes we might expect of them? Or do their experiences open up new worlds for us?

That brings me to the subject of mentors, heroes, and teachers, the people who at some formative moment in our lives open up new possibilities for us. This theme has fascinated me so much that it is a common thread throughout all of my oral history books.

I ask the people I interview to tell me about their heroes or mentors, because the answers are likely to reveal a great deal about both the person and his or her enthusiasm. For instance, the late Guy Anderson, one of the artists in our " Northwest School " of Puget Sound painting, once told me that, "You can have strong primitive urges but not be naive." He meant that, just as the Northwest coastal Indians had used "heavy, rich designs and color," he and other Northwest artists, such as Mark Tobey and Morris Graves, used the visual language of the Northwest in a sophisticated way. Guy said that he had been inspired in this direction at an early age by one of his high school teachers in Edmonds who had been to the Orient.

Guy Anderson had strong opinions about how we are influenced by our teachers and mentors (my favorite question in this book). He said that any art teacher who did not expose students to ten thousand years of art was "criminal." "Students need such a broad background," he said, "to make a great creative contribution. They'll find their own way if they are honest."

The question of heroes and mentors gets to the heart of the human condition. Whistlepunks and Geoducks is not designed to be parochial reading. I have sought universal significance in the particular. What were the influences which led a Guy Anderson in his chosen direction; what influences are likely to affect us?

I was born north of Seattle and raised here. We spent a lot of time hiking the mountain trails in the Cascades and Olympics. So there is something distinctly characteristic of the region in my work. Rich colors, etc. We do have that feeling of relationship.

We always felt the California School was very different. They've always used much brighter and sunnier colors. Everything looks darker and richer in heavy rains. The Japanese painted in rich, somber colors. Rock formations. Mossy vegetation. I've found at many times on Mount Pilchuck.

I am always looking to see how the twig was bent. I am always hoping to find stories that are like treasures out in plain sight. But do not be fooled by me into thinking that this search is easy. Many a tale has escaped as I have roamed from the Palouse to Puget Sound. The most frustrating cases were people who simply did not want to talk; the saddest were when someone had died who was an irreplaceable part of Washington.

For instance, Mary Wurth was ninety-two when she spoke with me on phone from her home in Spokane A blizzard prevented me from visiting her immediately. Then--suddenly it was too late.

Until her death Mary Wurth had been a stalwart member of Spokane's chapter (organized in 1883) of the Women's Christian Temperance Union, the anti-alcohol crusade of legendary saloon-smasher Carrie Nation. As a child Mary Wurth had met her heroine and now owned a genuine Carrie Nation hatchet.

How I wanted to see that hatchet and to sense the old fires glowing in Mary Wurth! Just before her death, the WCTU's Spokane chapter had voted to change its motto from "agitate, educate and legislate" to "educate, legislate and energize."

"I didn't like it one bit," said the woman whose mentor was Carrie Nation. "I didn't want to drop agitate from our stationery and I don't think we should stop [agitating]. I think we ought to get out there today and do a little more agitating."

Each time someone dies, an irreplaceable world disappears.

The Northwest, as historian Robert Cantwell explained in The Hidden Northwest, is such a new region that it has produced less a body of literature than a mass of personal experience from those who sailed, traded, farmed, trapped, invented, preached, and fought their way into what had been the Oregon Territory.

Whistlepunks and Geoducks is my latest effort to record that experience. It grew out of my own 1970 goal to walk from the Idaho border to the Pacific Ocean. By 1977, with many Pacific Northwest Trail treks behind me, I became a permanent resident, moving out from that other Washington on the Potomac. But somehow I was never content just to be in Washington state. I was always trying to explain it to myself and to others

Today, more than twenty years after my first adventures here, I still get excited when I return from afar and cross our state's border. When I arrive by plane, the first whiff of our air always invigorates me. Arriving by car, I am thrilled by the sight of so many Washington license plates on the road. If I arrive on foot, he day suddenly glows with new pleasure as soon as I realize that I am home.

Washington is not easily summed up, even by someone like me who has literally walked every foot of the way across the state to see the sun set over the Pacific Ocean. As painter Guy Anderson told me a decade ago, "I'd like the south of France for two or three years, but then I'd return to La Conner. Not even if I were terribly rich, would I leave here permanently."

"A rich and fascinating portrait of Washington life… [Strickland's] quiet introduction weaves the narratives together in a powerful harmony of memory, reflection, and wisdom."

"Memory, experience, and the narrative urge are the raw materials which novelists, poets, entertainers, and balladeers carve and burnish into rich gems of invention. I believe that at its best nothing can surpass the warmth and drama of a single voice speaking directly to us of the things which matter… Our impersonal age cries out for this balm, the healing touch of words, the storyteller's art."