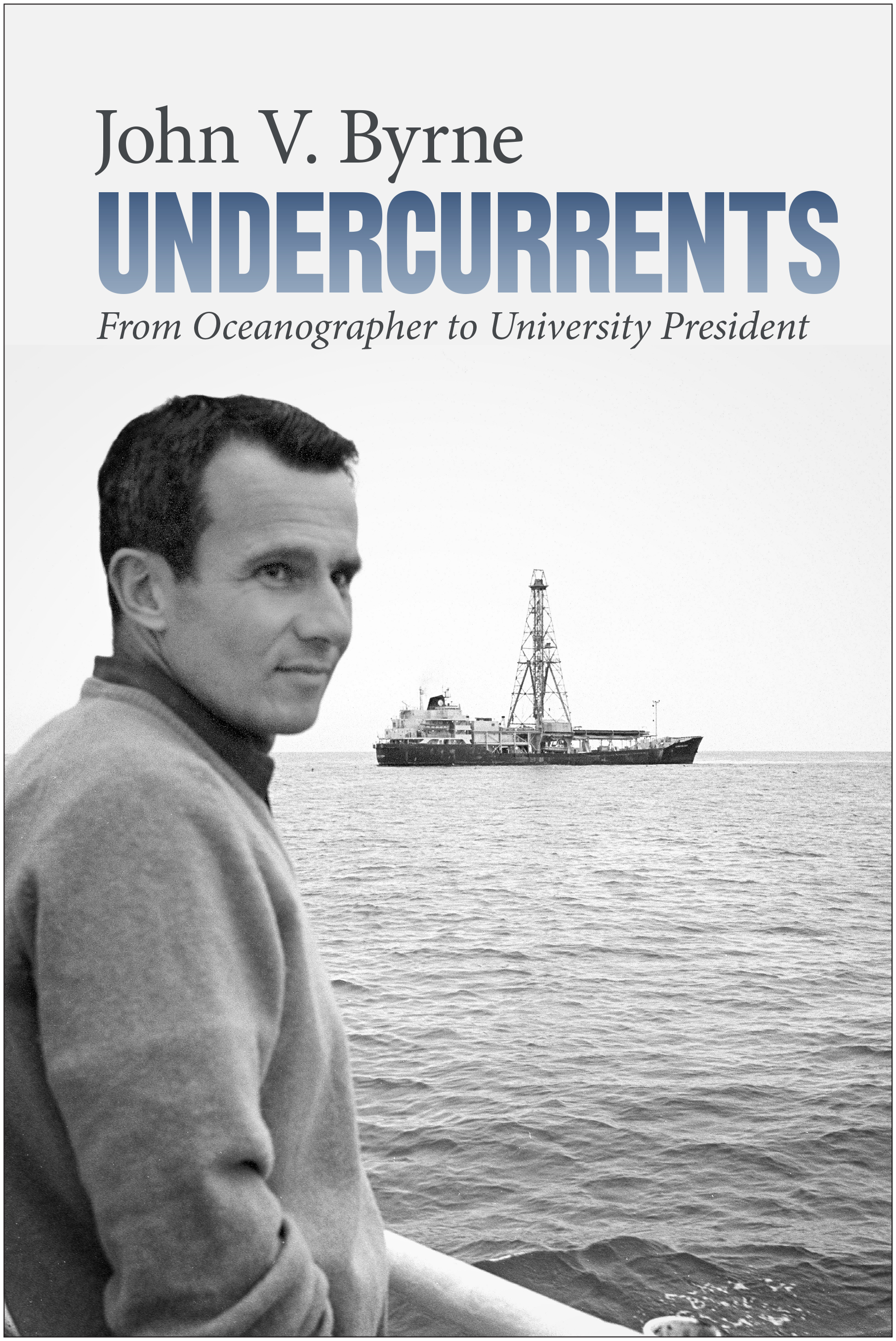

In this week’s two-part blog post, we take a look back at OSU Press author and Oregon State University Emeritus President John Byrne’s November 2000 speech titled “The University of the Future.” As we celebrate Oregon State’s 150th year as a land grant institution, John’s historic words demonstrate the ways in which OSU is living up to its mission to conduct world-leading research, to provide the highest quality education for the people of our state and beyond, and striving to be a “University of the Future” that is making an impact locally and globally. For more on John Byrnes’ philosophy on higher education, check out his newly released book, Undercurrents: From Oceanographer to University President.

In this week’s two-part blog post, we take a look back at OSU Press author and Oregon State University Emeritus President John Byrne’s November 2000 speech titled “The University of the Future.” As we celebrate Oregon State’s 150th year as a land grant institution, John’s historic words demonstrate the ways in which OSU is living up to its mission to conduct world-leading research, to provide the highest quality education for the people of our state and beyond, and striving to be a “University of the Future” that is making an impact locally and globally. For more on John Byrnes’ philosophy on higher education, check out his newly released book, Undercurrents: From Oceanographer to University President.

______________

From: “The University of the Future”

A Keynote Address presented to The Alliance of Universities for Democracy

Eleventh Annual Conference

By: John V. Byrne

Emeritus President, Oregon State University

November 5, 2000

The challenges to sustain a healthy world population and the opportunities associated with these challenges is greater than humans have ever faced before, and they will continue to increase. But the knowledge needed to address the challenges is also increasing exponentially. It is estimated that the totality of world knowledge doubled between 1750 and 1900, that by 1965 world knowledge was doubling every five years, and that by 2020 the totality of world knowledge will double every seventy-three days. How that knowledge is used will be determined by those who are prepared to use it. Our colleges and universities will be critical to meeting those world challenges and using the newly created knowledge. If higher education is to respond effectively to the challenges created by the world population explosion and the opportunities provided by the rapidly available knowledge it will be required to change the way it operates. Higher education must constantly re-assess the way it functions in order to keep abreast of the rapidly changing world of which it is such an important part.

In recognition of the unprecedented speed of change within society and the need for American public universities to be increasingly responsive to the needs of the society they serve, the Kellogg Commission on the Future of State and Land-grant Universities was created with funding from the W. K. Kellogg Foundation. The Commission consisted of the presidents and chancellors (past and present) of twenty-six American public universities. Seven non-academic advisors met with the Commission to provide the citizens’ perspective. The Commission’s goal was to stimulate change and reform through discussion and action on public university campuses. The Commission was created at time when a skeptical public appeared convinced that students were being ignored and that research was more important than teaching, when enrollment was projected to increase significantly at the same time that funding was limited and would continue to be so, when society was facing staggering changes in values and family structure, and when new educational entities, such as community colleges, corporate universities, and for-profit institutions, had entered the student market place. The Commission was to meet four times per year, with the charge to address the reform of American public higher education.

The Commission’s first meeting was held in January 1996 and its final meeting in March 2000. At that first meeting the Commission identified five issues for discussion and campus action: The Student Experience; Access; The Engaged Institution; A Learning Society; and Campus Culture. Letter-reports were published regarding each of these issues. Later, a sixth report about the partnership between the public and its universities was published, “Renewing the Covenant: Learning, Discovery, and Engagement in a New Age and a Different World.” The Commission addressed “The Student Experience” first because students are fundamental to the existence of universities.

As the Commission considered “Access” it became readily apparent that the issue was really not access or admission to our institutions, but, more importantly, access to a successful life in society resulting from a higher education experience. Access to such a life is affected by admission policies and guidelines, by retention, and by the student’s achievement of his or her educational goals.

The Commission’s discussion of “The Engaged Institution” focused on the role of public universities in reaching beyond their campuses and joining in partnership with those elements of society, which benefit from a shared endeavor.

During the discussion of “A Learning Society” the evolving nature of society into a true learning organization was noted. Such a society is characterized by the ability to create and use new knowledge for society’s benefit and to organize opportunities for individuals to continue to learn throughout their lifetimes: “lifelong learning.”

In addressing “The Campus Culture” the Commission noted that, in order to be more responsive to the increasingly rapid pace of change in society, universities themselves must change, and must do so rapidly. Their operation must become more effective, more efficient, and more flexible. In the past, as universities have responded to the many demands of society, they have evolved into institutions with many different cultures rather than one single culture: an academic culture, made up primarily of faculty and students, but with subcultures organized around disciplines; a separate student culture; an administrative culture; an athletic culture. A challenge before American universities is to integrate the elements of these diverse cultures into a single all-inclusive campus culture that mediates and bridges the diversity of cultures and is consistent with the aims and mission of American public higher education.

In recent years the differences between American private and public universities have become less evident. As state support for public universities has diminished, public universities have turned more and more to private funding. Research universities, both public and private, rely on external funding for support of research. All major universities today provide services to their societies, all are engaged with the public. Although the ideas expressed by the Kellogg Commission apply directly to public universities, most of these ideas apply equally well to private universities. This paper offers guidelines for the successful University of the Future, public or private, in the context of a rapidly evolving global Learning Society, and is based to a considerable degree on ideas expressed by the Kellogg Commission.

A Learning Society

Education and the ability to learn are essential in a world in which new knowledge increases at an exponential rate and the ability to use that knowledge is critical to the social, economic, and political health of individuals, the nation, and the world. The university must provide leadership as society rapidly adopts the characteristic elements of a learning organization and becomes a “learning society.”

A learning society is a society that values and fosters habits of lifelong learning and ensures that there are responsive and flexible programs and networks available to address individual and organizational needs. A learning society is socially inclusive and ensures that all of its members are part of its learning communities. It recognizes the importance of early childhood development as part of lifelong learning and develops organized ways of enhancing the development of all children. Further, a learning society stimulates the creation of new knowledge through research and other means of discovery and then uses that knowledge for the benefit of society. It values regional and global interconnections and cultural links, and views information technologies, including all interactive multi-media technologies, as tools to enrich learning. A learning society fosters a public policy agenda that ensures equity and availability of learning for all and contributes to the over-all competitiveness and economic and social well-being of the nation.

In the context of a learning society, the successful university of the future will provide learning opportunities for its students, wherever those students may be, and will prepare them for engagement in an ever-changing society, in which the ability to learn throughout each student’s life is essential. In a learning society, lifelong learning is a part of the societal ethos.

Basic Ideals

In recognizing the needs of the global society the university of the future will be based on seven broad ideals:

First, universities, particularly public universities, must provide equal access to all who are qualified. Society needs the talent of all its people. We cannot make the mistake of ignoring the educational needs of large portions of our population without exacting an enormous price from ourselves in terms of lost ability and missed opportunities. What we are talking about is individual access to success through higher education, not simply access to higher education but access to the full promise of life;

Second, our colleges and universities must become genuine learning communities, which support and inspire faculty, staff, and learners of all kinds. The emphasis will be on learning by all members of the institutional community: students, and faculty and staff. As a community, all will contribute and all will benefit;

Third, our learning communities must be student-centered, committed to excellence in teaching and to meeting the legitimate needs of students (i.e. learners) wherever they are, whatever they need, and whenever they need it;

Fourth, we must emphasize the importance of a healthy learning environment that provides students, faculty, and staff with the facilities, support, resources, and attitudes essential to making the vision of a successful life a reality;

Fifth, our universities must be responsive to public needs, intimately engaged with the societies they serve. It is time to reach beyond outreach and extension to what the Commission has defined as “engagement”;

Sixth, universities must emphasize and instill moral and social values in students, faculty, and staff through their pedagogies and through their actions;

Seventh, universities must be active participants in promoting civility in the society they serve and must extend their efforts to promote civil societies globally.

Universities must affirm these ideals, adhere to them tenaciously, and follow their implications faithfully wherever they lead. Only through such constancy of purpose will the university of the future effectively serve its local society, its nation, and the world.

END PART 1… Check back next week for Part 2 from John Byrne’s speech “The University of the Future.”