Henry

Zenk, co-translator with Jedd Schrock of My Life, by Louis Kenoyer: Reminiscences of

a Grand Ronde Reservation Childhood, is here to explain the complicated

and painstaking process he and Jedd Schrock undertook when translating the reminiscences

left by Louis Kenoyer. Kenoyer was the last known speaker of Tualatin Northern

Kalapuya, the language in which he dictated his memoir, describing life and

recounting his childhood o n the Grand Ronde Reservation in Oregon in

the late 19th Century. Zenk

and Schrock were confronted with what many may have found to be an overwhelming

obstacle: the linguists whose manuscripts they worked from left them with an incompletely translated text, but did not provide them with a usable description of the language’s

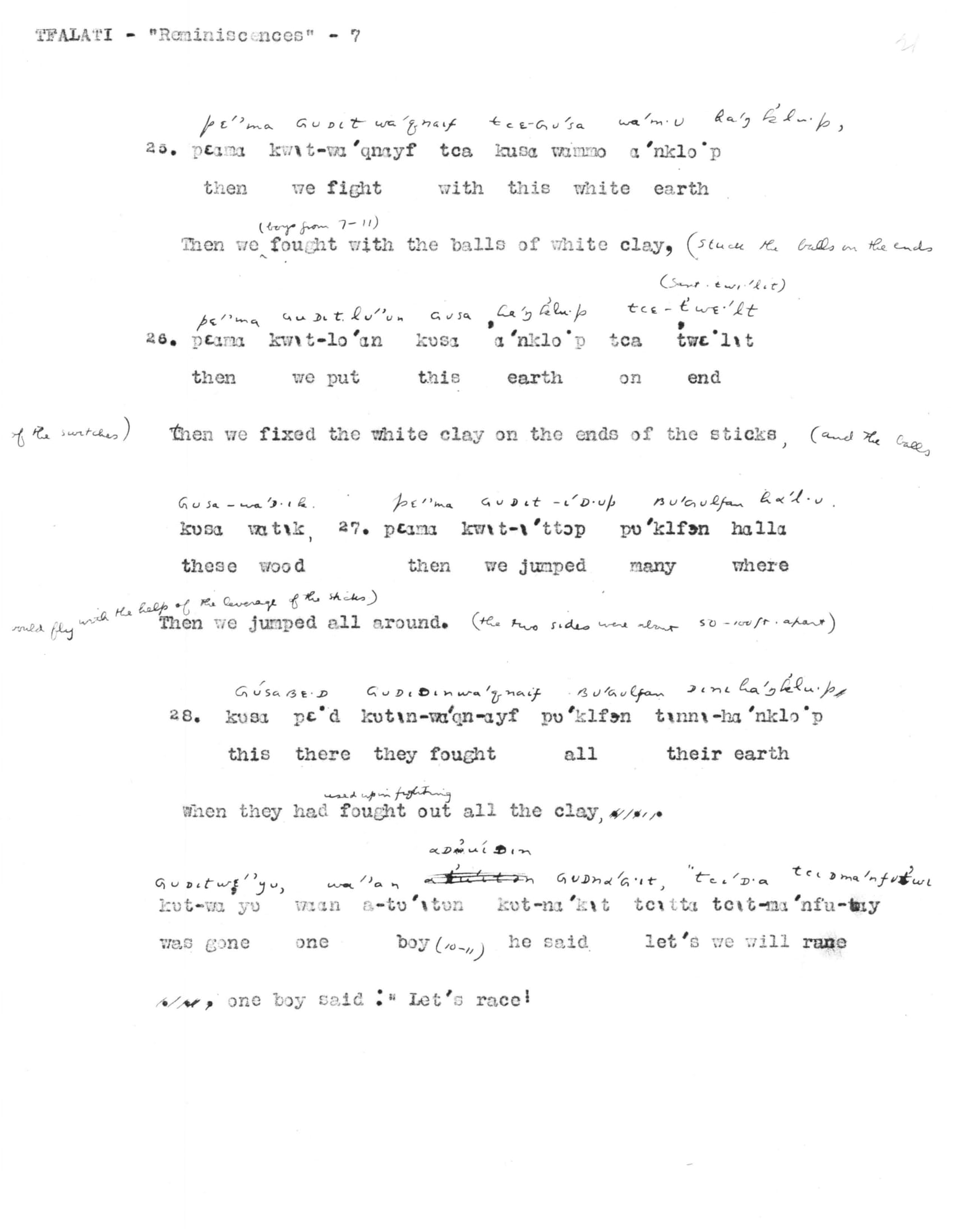

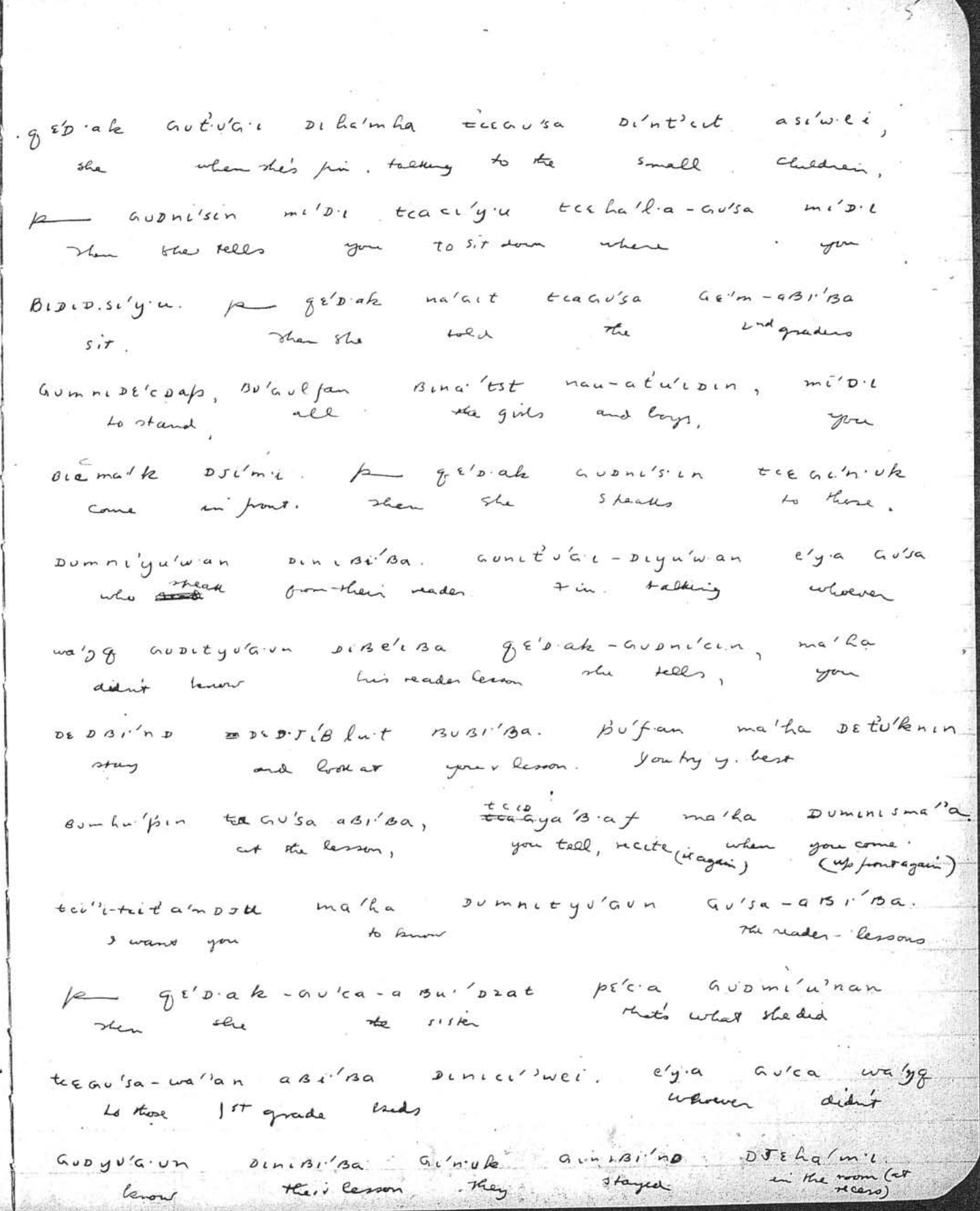

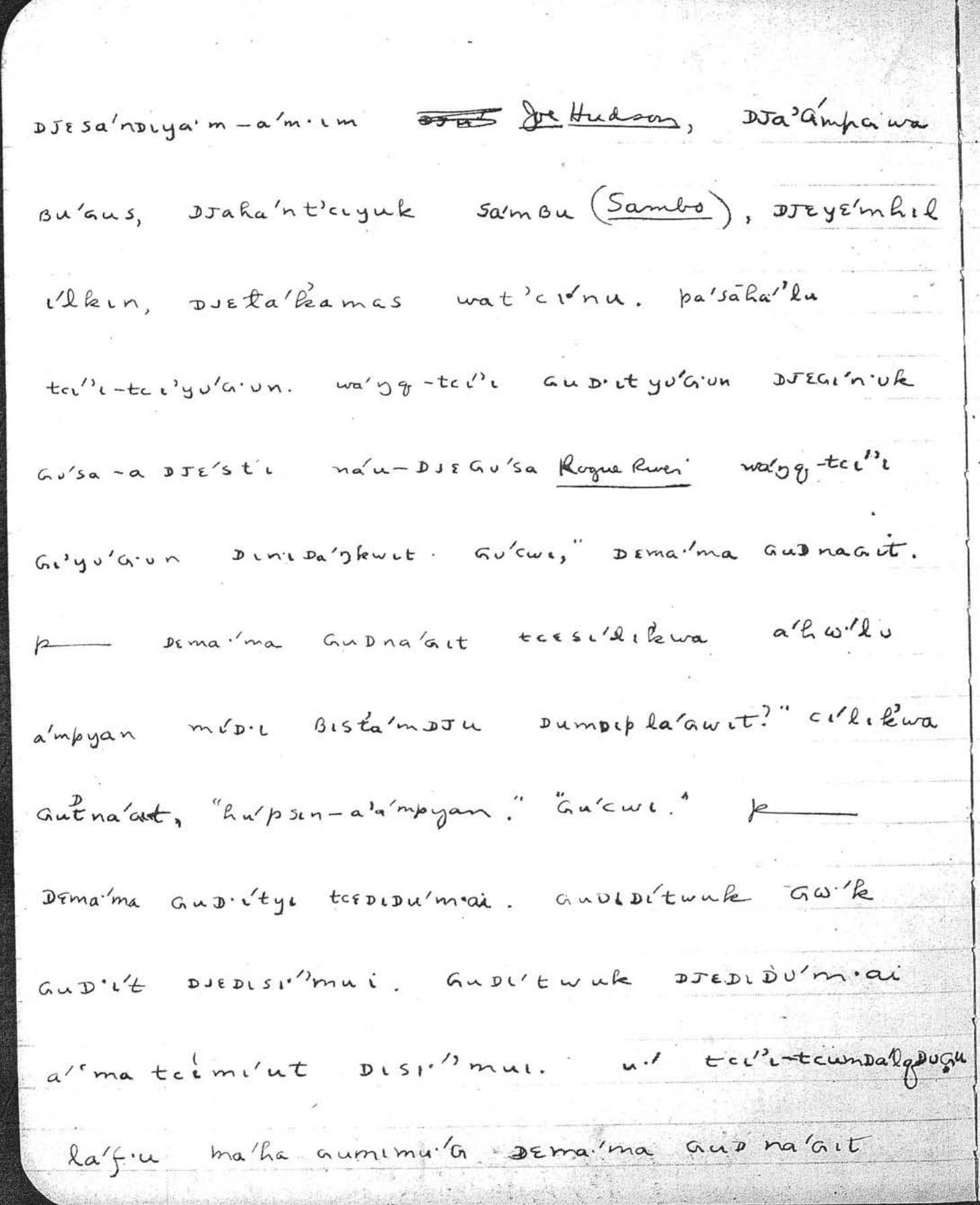

grammar. The illustrations below sample the record left by the three linguists whose manuscripts Zenk and Schrock worked from: first, a typescript-page with interlinear and free translations; next, a field-notebook page with field translation; and finally, a field-notebook page minus translation.

----------------------

The subject

matter of My Life, by Louis Kenoyer is

a long autobiographical narrative told in Tualatin Northern Kalapuya, the

indigenous language of one of the founding tribes of the Grand Ronde

Reservation community. The narrative was dictated to three linguists by that

language’s last known speaker, Louis Kenoyer, who died in 1937. Jedd Schrock

and I undertook this task without the benefit of a proper formal description of

the language’s morphology and syntax. While the three linguists who worked with

Kenoyer left us an abundance of texts and word lists, they apparently devoted little

attention to ferreting out subtle variations of linguistic form, as visible notably

in the many permutations of recurring elements constituting its verb  prefixes. This

prefixes. This

seems a good time to pause and reflect on just how we managed to understand

Tualatin well enough to translate it into English, lacking a formal description

of the language’s grammar.

The main

key to our translation resides in the three linguists’ field translations,

given by Kenoyer himself as the linguists read back the Tualatin text they had

just transcribed from him. There are some complications, however. For one, the

last quarter of the narrative (60 pages of bilingual English-Tualatin text as published)

lacks a field translation, being preserved only as a Tualatin-only phonetic

transcript in the field notebooks of Melville Jacobs, the linguist to whom we

owe the final form of the narrative. For another, the field translations are

rather free. To some extent, this reflects the fact that Kenoyer was quite comfortable

using English, in which he was not only fluent but also literate (owing no

doubt to a youth spent largely in government boarding schools, one of the main subject-matters

of his narrative). In common with all Grand Ronde Indians of his generation, Kenoyer

had also used Chinuk Wawa from childhood, a circumstance of some significance I

believe. I was fortunate to have heard Chinuk Wawa from some of the last fluent

elderly speakers of Kenoyer’s home community of Grand Ronde, among them

Kenoyer’s step-niece, Clara Riggs. This experience has enabled me to recognize

not only Chinuk Wawa words that Kenoyer used as part of his Tualatin (and there

are quite a few of those), but also, what I take to be evidence of deeper influence

affecting his Tualatin word orders.

The main

difficulty confronting any attempt to use Kenoyer’s field translations to

decipher his morphology is that his field translations are not literal. When

translating his dictations as they were read back to him, Kenoyer was clearly

more concerned to produce an intelligible, colloquial English, than he was to

register minute differences of morphological form. What we really need is a

living, fluent speaker, with whom to explore such fine distinctions in an

experimental spirit. Through a process of trial and error, we might hope to

tease out the nuanced meanings lent by a speaker’s selections of particular

prefixes and suffixes to express particular meanings in particular contexts.

While that can be quite a long drawn-out process, it leads to the most

trustworthy results. If you have any such speaker for the indigenous language

you are studying, take very good care of that speaker—he or she is gold! We

don’t have that for Tualatin, nor for any of the other Kalapuyan languages.

What we can

do, and what Jedd and I indeed did do in preparing Kenoyer’s narrative for

publication, is to use the field translations of the translated parts of the

narrative as a basis for translating its untranslated parts. In the process, we

each developed our own working hypotheses for identifying and interpreting

contrasting word-forms in Jacobs’s transcriptions (unfortunately, we have no

(unfortunately, we have no

audio of Kenoyer from which to form our own judgments). These hypotheses were

informed by available linguistic work on Kalapuyan languages, primarily

analyses conducted on the neighboring Central Kalapuya language. We tested our individual

working hypotheses against the untranslated text, then took them back to the

translated text to see how they stacked up against Kenoyer’s field

translations. This created a mutually reinforcing feedback loop, the ultimate

result of which is that we must take the main credit—or blame—for the final

form of the finished translation. Our independent translations of parts of the

untranslated text came out looking very similar in all cases, giving us a high

degree of confidence in the final product. While we must grant that an improved

control of the morphology would permit a further sharpening of the translations,

we feel that our translations compare favorably on that score to Kenoyer’s own field

translations.

Speaking

for myself, I would describe the translation process as a kind of gestalt

exercise. This was most true, not surprisingly, for the untranslated sections

of the narrative. Fortunately, a full 99% of the word-stems appearing in these

sections were identifiable from the translated sections. But it isn’t enough to

take a segment of untranslated text, and simply string together glosses

(readings) pulled from the translated sections of the narrative. While we may

not grasp all of the nuances conveyed by variations in the form of, for

example, the verbal prefixes, we do have non-literal English glosses from

Kenoyer’s translations to go with practically every recorded variation. For

more frequently used forms, we have a range of such glosses. Moreover, with

respect to the verbal prefixes in particular, those in Kalapuyan languages are

characteristically multi-functional. A particular prefix or prefix complex

typically combines reference to the subject of the verb action with its temporal

and modal characteristics (tense and aspect, actuality or potentiality of

realization, etc.). The decision of which gloss from the range of recorded

glosses to apply to a particular form in a particular case requires close

attention to the narrative context.

In some

cases, it would be virtually impossible to divine the intended meaning of a

form or expression, lacking clues from the field translation. For example, among

Kenoyer’s many borrowings from Chinuk Wawa is the noun “pipa.” Usually, “pipa” carries

the same range of

meanings in his Tualatin that it does in Chinuk Wawa: “paper,

meanings in his Tualatin that it does in Chinuk Wawa: “paper,

letter, document, book”; only Kenoyer uses it in some sections of the narrative

with the extended meanings “reader” (that is, lesson book) and “grade level”

(referring to which graded reader a student in the reservation boarding school

is up to). The untranslated text segment describing daily lessons in the

reservation boarding school would be very opaque indeed, had we not a preceding

translated section in which “pipa” is used explicitly with reference to

students’ grade levels.

The

relevance of Chinuk Wawa to Kenoyer’s narrative is apparent not only with

respect to borrowings used to express key concepts, as in the above example.

One of the things that struck me personally is how suggestive Kenoyer’s

Tualatin word orders are of Chinuk Wawa word orders: grammatical subjects

precede the verb; grammatical objects usually follow the verb, but can be

fronted for focus; temporal adverbs and adverbial phrases usually come

clause-first, or occasionally, appear in clause-final position; there is a

single universal preposition. While subject-verb-object order is equally

characteristic of English, the other features are less so. By contrast to his highly

uniform and predictable word orders, Kenoyer’s verbal morphology reveals many

indications of inconsistency and irregularity: prefixes are usually, but not

invariably present, and come with many variant forms; productive suffixes are

few, and appear only sporadically. We need more comparative work on Kalapuyan

to tell how unique Kenoyer’s Kalapuyan is in these respects. My own experience

was that upon immersing myself in his Tualatin narrative, I began finding it surprisingly

readable, a development that I am inclined to attribute to its uniform (and,

significant to my mind at least, Chinuk-Wawa congruent) word orders. By the

time we got to the final stages of preparing the narrative for publication, I

was able to sit down with the Tualatin text and proof it without reference to

the translations. This has left me in the rather peculiar position of having

achieved a real feeling for this language—only please don’t ask me to explain (in

too much detail, anyway) exactly just what are all those prefixes doing!