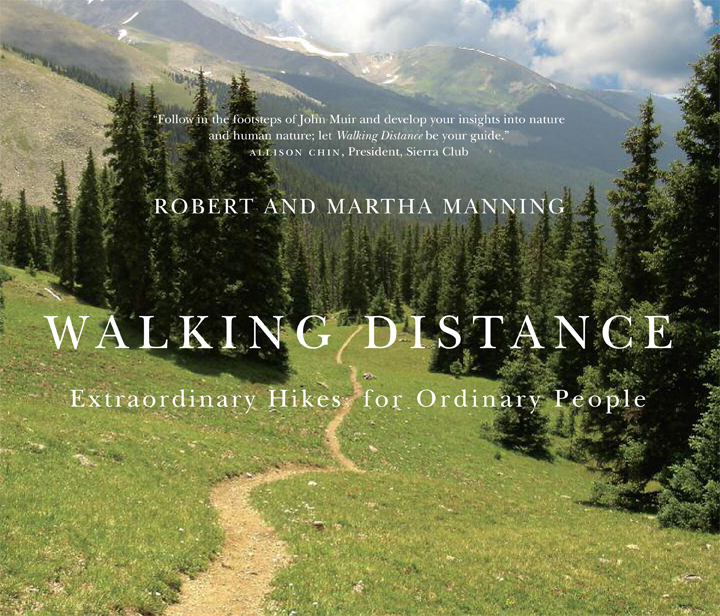

Today we're pleased to share a preview of Robert and Martha Manning's new book, Walking Distance: Extraordinary Hikes for Ordinary People—just announced as a finalist for a Book of the Year Award. This essay, adapted from the book, was originally published in the Chronicle Review on December 10, 2012.

One of my favorite parts of the day is the half-hour walk between my home and campus, when I reflect on my teaching and research. Lately I've been walking farther, hiking some of the world's great long-distance trails—across England, around Mont Blanc, along the coastlines of North America and Australia, among the world's iconic mountains, including the Appalachians, Rockies, Sierra Nevadas, Alps, and Andes. Every day on the trail is an adventure that engages me both physically and intellectually.

There has been a long and productive association between walking and thinking. Some scholars believe that relationship can even be traced to human evolution. The paleoanthropologist Mary Leakey, for example, suggests that bipedalism freed the hands of protohumans for toolmaking and other advantages, and that the brain expanded exponentially to meet that opportunity. Walking and thinking are defining characteristics of what makes us human.

Moreover, walking is a miracle—a biomechanical marvel. Most of us take it for granted—it's "pedestrian." But it's a symphony of moving parts involving our highly developed nervous, skeletal, and muscular systems and both the balance and the strength to hold ourselves upright on two relatively small feet, all while moving one foot in front of the other for miles on end, over varied terrain, without falling, and doing so with little conscious thought.

The aesthetics of walking entered the popular imagination in the 1880s with the publication of Eadweard Muybridge's photographic "motion studies," which used a battery of linked cameras to record the act of walking. Geoff Nicholson writes in his book The Lost Art of Walking that for him, those "walking pictures reveal the magical nature of something we take so much for granted."

Whether or not walking contributed to the development of our brains, there's no question that it has stimulated our thinking. Aristotle walked as he thought and taught in the Lyceum of ancient Athens, founding the Peripatetic school ("peripatetic" meaning "one who walks"). Recent examples include the philosophers and writers of the Romantic movement in the 18th and 19th centuries. The philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau set the stage for Romanticism by questioning Western society's march toward increasing industrialization and urbanism. In his book On Foot: A History of Walking, Joseph Amato calls Rousseau "the father of Romantic pedestrianism." Rousseau's principal works, The Confessions and Reveries of a Solitary Walker, encouraged readers to return to nature and simplicity and were informed by his own long walks. "There is something about walking that stimulates and enlivens my thoughts," he wrote. "I can only meditate when I'm walking. ... When I stop I cease to think; my mind works only with my legs."

Other great walker-thinkers of the Romantic period include Wordsworth, Thoreau, and John Muir. Wordsworth's colleague Samuel Coleridge estimated that Wordsworth walked 180,000 miles over his adult life. Wordsworth apparently had the ability to develop insights and compose poetry while he walked. Christopher Morley wrote, "I always think of him as one of the first to employ his legs as an instrument of philosophy." It's reputed that when a traveler asked to see Wordsworth's study at Dove Cottage, his home in the Lake District, his housekeeper replied, "Here is his library, but his study is out of doors."

Thoreau took up the Romantic mantle in America, walking throughout New England, especially around his home in Concord, Mass., and his retreat at Walden Pond. Eloquent (but often cranky), he advanced his transcendental philosophy, urging Americans to preserve remaining pockets of nature and to walk in the landscape to find manifestations of God and higher truths. In his essay "Walking," he wrote, "I think I cannot preserve my health and spirits, unless I spend four hours a day at least—and it is commonly more than that—sauntering through the woods and over the hills and fields, absolutely free from all worldly engagements." In his sometimes arrogant but endearing way, he claimed to "have met but one or two persons in the course of my life who understood the art of Walking, that is, of taking walks—who had a genius, so to speak, for sauntering."

John Muir carried the Romantic tradition westward, walking a thousand miles from Indiana to the Gulf of Mexico as a young man, then hiking in the Sierra Nevada of California for much of his life. His walks offered him deep insights into our relationship with the natural world, and he used walking as a metaphor a year before he died, when he wrote that "I only went out for a walk, and finally concluded to stay out until sundown, for going out, I found, was really going in."

The rich set of ideas associated with walking, along with the act of walking itself, has advanced an array of political causes. For example, the Romantic philosophy of Rousseau suggested an inherent value in the individual, which in turn offered a powerful argument against the tyranny of a wealthy minority. Those ideas helped inspire the Women's March on Versailles, in 1789, to protest the scarcity and price of bread—an important precursor to the French Revolution.

Other examples include Gandhi's 240-mile Salt March, in 1930, protesting British taxes; Martin Luther King Jr.'s 54-mile march, in 1965, from Selma to Montgomery, Ala., to protest unjust voting laws; and Cesar Chavez's 340-mile March for Justice, in 1966, to protest mistreatment of farm workers in California. It's no coincidence that the autobiographies of King and Nelson Mandela are titled Stride Toward Freedom and Long Walk to Freedom, respectively. Rebecca Solnit speaks to the power of walking in her book Wanderlust, where she writes that "walking becomes testifying."

One of the political causes closest to many walkers is conservation. It was the Romantics who sent legions of walkers out of their gardens into the wider, wilder landscape in search of beauty and solitude. Thus walking evolved into an activity in itself, not just a means to an end. Of course, that meant that walkers needed wild places to walk in. Walkers banded together in what have become powerful social forces for environmental protection, such as the Appalachian Mountain Club (founded in 1876) and the Sierra Club (founded in 1892).

Walking and conservation have a parallel track in cities as well as in wilderness. In fact, it's not uncommon to read about urban areas as wilderness of a different kind. Walking in cities also appeals to those with a sense of adventure. In Paris, it was the flâneur—literally a stroller—who, in the 19th century, became the archetypal bohemian, famously explored the city's nooks and crannies at leisure, and, in the words of Walter Benjamin, went "botanizing on the asphalt."

Charles Dickens may have been the ultimate urban walker, logging as many as 20 miles a day in his native London. Those rambles not only gave him welcome respite from his writing desk but also enlivened his work with the grim details of city life that made his novels famous. The literary critic Alfred Kazin's A Walker in the City (1951) is a classic portrait of the intellectual as a young man, making the literal and metaphorical journey from his working-class Jewish roots in Brooklyn to redefine himself in the wider world of Manhattan, standing in for an intellectual community.

Walking has a strong spiritual dimension as well, epitomized by the pilgrimage. Seekers have been walking for centuries for spiritual enlightenment. The oldest and largest pilgrimage is the hajj; all Muslims who are physically able and can afford to do so must travel to Mecca, in Saudi Arabia, at least once in their lifetimes. More than a million pilgrims participate in the hajj every year. Some Muslims say ritual pilgrimages to Mecca originated in the time of Abraham.

Christians began making pilgrimages to Rome, Jerusalem, Santiago, and other holy sites in medieval times. Such pilgrimages are experiencing a renaissance, and not just for Christians. Nor is walking meditation, in which the walker focuses "mindfully" on the experience of walking itself, just for Buddhists. There is even now a labyrinth movement; according to the Web site Veriditas, "Walking the labyrinth reduces stress, quiets the mind, grounds the body and opens the heart."

Walking is simple; it's analog in a digital world, as Nicholson writes. But it can also be profound. Walking celebrates our evolutionary heritage; it's a biomechanical and aesthetic triumph as well as a form of political expression. It stimulates art, deepens our understanding and appreciation of the natural and human worlds, and attunes us to our own spirituality. All while making us healthier and happier.

But above all, walking is a choice we must consciously make. In today's world it's easier, more convenient, to sit and ride. History suggests that long walks can lead to deep thoughts, but to be so enriched, we must "walk the talk."

—Robert E. Manning

Related Titles

Walking Distance

Walking is simple, but it can also be profound. In an increasingly complex and frantic world, walking can simplify our lives. It encourages intimate contact...