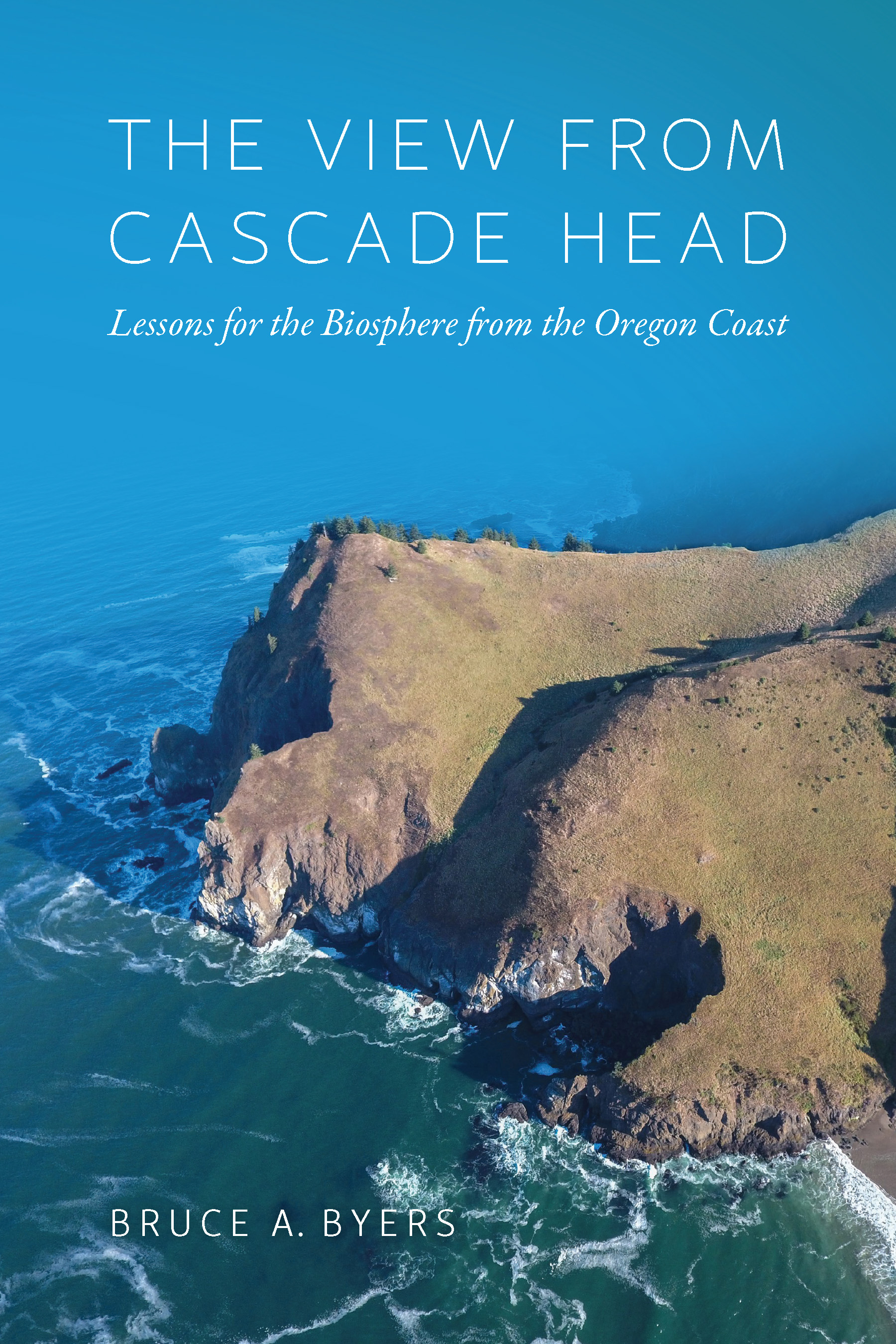

In celebration of University Press Week, our guest blogger for today is Bruce A. Byers, author of The View from Cascade Head: Lessons for the Biosphere from the Oregon Coast. In today's post, he talks about the genesis of his book, the beauty and ecological significance of the Oregon Coast, and the importance of nature-writing to science and the conservation movement. He also reflects on Oregon's recent wildfires and what the future may hold.

* * * * * * *

Though born in Oregon, I grew up and have mostly lived elsewhere. But some of my earliest and fondest memories are of poking in tide pools with my grandfather on summer visits to the Oregon Coast. Those tide pools gave a glimpse into another world. It seemed to me a huge, beautiful, nonhuman world of scuttling hermit crabs, snails, camouflaged fish, and flower-like anemones. Multi-colored seastars crammed in every crevice and crawled on every rock. I remember a special delight in their diverse colors—brown, orange, and some a deep, royal purple, like the color of the robes of the ancient King of the Sea. I think that was the seed of my sense that the world is a wide and wondrous place, way beyond our grasp of it or influence on it, and that everything is connected to everything else. After I got a PhD in ecology, I remember blurting out, when someone asked me, “Well, how did you come to be an ecologist?” that it was all because of my granddad, and the tide pools at Haystack Rock. Later I wondered, Did I really mean that—that I became an ecologist because of those experiences starting at five years old? And when I thought harder and deeper about it, all I could come to was—Yes!

beautiful, nonhuman world of scuttling hermit crabs, snails, camouflaged fish, and flower-like anemones. Multi-colored seastars crammed in every crevice and crawled on every rock. I remember a special delight in their diverse colors—brown, orange, and some a deep, royal purple, like the color of the robes of the ancient King of the Sea. I think that was the seed of my sense that the world is a wide and wondrous place, way beyond our grasp of it or influence on it, and that everything is connected to everything else. After I got a PhD in ecology, I remember blurting out, when someone asked me, “Well, how did you come to be an ecologist?” that it was all because of my granddad, and the tide pools at Haystack Rock. Later I wondered, Did I really mean that—that I became an ecologist because of those experiences starting at five years old? And when I thought harder and deeper about it, all I could come to was—Yes!

For my PhD research, I returned to the Oregon Coast to study an intertidal snail because it was a good species in which to understand the ecological and evolutionary dimensions of the question “Is behavior ecologically adaptive?” In retrospect, I’ve come to see, over the rest of my career, that I really wanted to answer that question about my own species, whose behavior seems in so many ways anything but ecologically adaptive and wise. But sometimes I get hints of hope that it can be—as I did when I spent some months living and working at Cascade Head recently as ecologist-in-residence at the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology.

Cascade Head is Oregon’s only biosphere reserve, part of an international network of biosphere reserves coordinated by the UNESCO Man and the Biosphere Programme. That program, and the concept of the “biosphere” from which it arose, are important achievements in the history of ecology, conservation, and sustainable development. Biosphere reserves are supposed to be laboratories for understanding the human-nature relationship, and models for other places to learn from as we all struggle toward a sustainable relationship between humans and our home planet. In my work as an international ecological consult, I’ve had the good fortune to spend time in thirty-four biosphere reserves in seventeen countries. Although each is unique, they all face similar challenges and provide lessons for all the others.

The interconnected essays in this book tell the as-yet-untold story of the Cascade Head Biosphere Reserve. I’ve tried to weave together personal observations and experiences, ecological science, the history and philosophy of nature conservation, and wider cross-cultural worldviews.

Place-based nature writing is, perhaps not surprisingly, almost synonymous with nature writing. From Walden to Wintergreen, and from The Island Within to A Wilder Time, classic nature writing has been grounded in a particular place. But a valid question is “How big is your place”? It’s very, very hard to draw boundaries around ecosystems. Place-based writing is appealing and can be lyrical because it shows readers the complex, wondrous particulars of a place. But where are the boundaries? When we probe for the ecological boundaries of any place, we find that they expand to the entire biosphere. I tried to write a place-based book full of all the enlivening details about the Cascade Head landscape and ecosystem, but then expand the story—to expand spatially, out beyond the horizon to the scale of the biosphere, and temporally too, to the scale of historical and evolutionary time. Beavers, butterflies, whales, and salmon all have ecological and evolutionary stories that illustrate what I call in the book “a prescription for correcting the ecological myopia of our own species.” I tried to follow the advice given by John Steinbeck and his marine ecologist friend Ed Ricketts in their little gem of a book, Log from the Sea of Cortez, which described a six-week marine intertidal collecting expedition they made together in 1940: “It is advisable to look from the tide pool to the stars and then back to the tide pool again.”

In looking from the near to far, and back again, I concluded that The Cascade Head Biosphere Reserve is a microcosm. It is only a tiny part of our planet’s thin and fragile living skin, but the efforts of many dedicated people to defend a balance between humans and nature there are illustrative and instructive. The lessons from Cascade Head apply anywhere.

Three lessons stand out. The first is the importance of individuals whose commitment, hard work, and love of place over many decades have made Cascade Head such a rich laboratory and model. Their stories are unequivocal in showing the importance of inspired, value-based, individual action. The second lesson is that although ecologists now understand much about how nature works, ecological mysteries still abound. We don’t fully understand the migratory traditions of gray whales, the causes of sea star wasting syndrome, the genetic diversity of the Oregon silverspot butterfly, the life histories of salmon, or the ecohydrology of forests. More research is needed to strengthen the scientific knowledge that underpins decisions about restoring ecosystems and maintaining their resilience in the face of the changes our species is creating in the biosphere. A third lesson is the importance of worldviews is how we think about the human-nature relationship—in shaping our individual and collective actions. At Cascade Head we can read the history of changing worldviews in the landscape, and begin to imagine how a new, ecocentric worldview could help heal the human-nature relationship here, and everywhere.

It used to be fashionable to talk about “the balance of nature.” But as ecologists have learned more, we realize that “balance” is not quite the right word; it can be misunderstood to suggest some sort of stability or stasis. Our home planet is dynamic and changeable, and old ideas of ecological “stability” have given way to a more sophisticated view of the dynamic balance—the resilience—of ecosystems. You can think of resilience as the kind of balance it

takes to ride a wave on a surfboard, not to stand still on a rock. On a planet prone to chaos, life has so far found adaptive pathways to survival, but humans have caused and accelerated global changes that now stress ecosystems in ways that threaten our own existence. If we are to survive much longer, we must rebuild the resilience of the ecosystems we have degraded.

Thinking about resilience, my mind immediately jumps to images of the wildfires Oregon experienced in the past few months. One, the Echo Mountain Fire, started about half-a-dozen miles east of Cascade Head in the valley of the Salmon River. The fire was relatively small, burning only around twenty-five hundred acres; it destroyed approximately three hundred structures—houses, shed, and barns—but no one lost their life.

For many people, the fires sparked fear, a sense that nature is changing, getting out of control. But fire has always been a natural part of the Cascade Head ecosystem, and has always been influenced both by climate and human activities. Forest ecologists estimate that natural fire return intervals in western Oregon forests like those at Cascade Head were two hundred years or more before Euro-American settlement, and that almost half the landscape would have been old-growth forest. Now, because logging mined out the old growth, little is left, and research has shown that much of the western United States is now in a state of “fire deficit” because of our ecologically unnatural forest management policies and practices, especially fire suppression.

The coastal grasslands that cover the scenic southern flanks of Cascade Head and are protected in The Nature Conservancy’s Cascade Head Preserve—a core part of the biosphere reserve—are in part the result of fires set by the Indigenous people who lived in the area. Those meadows are the prime habitat for the threatened Oregon silverspot butterfly, and are now maintained and managed with prescribed, controlled burns. The last major fire to touch Cascade Head was the Nestucca Fire in 1845, which burned and reset ecological succession on about two-thirds of its forests. Forests are resilient, and biodiversity thrives in a landscape that is a mosaic of all stages of ecological succession. We have work to do to reconcile our relationship to wildfire. It’s we who need to adapt, and, through research and restoration, bring back more of the natural diversity and resilience of our forests. Fire will have to have a role in that process, and in understanding that role, Cascade Head and its biosphere reserve can continue to be a laboratory and model.

The coastal grasslands that cover the scenic southern flanks of Cascade Head and are protected in The Nature Conservancy’s Cascade Head Preserve—a core part of the biosphere reserve—are in part the result of fires set by the Indigenous people who lived in the area. Those meadows are the prime habitat for the threatened Oregon silverspot butterfly, and are now maintained and managed with prescribed, controlled burns. The last major fire to touch Cascade Head was the Nestucca Fire in 1845, which burned and reset ecological succession on about two-thirds of its forests. Forests are resilient, and biodiversity thrives in a landscape that is a mosaic of all stages of ecological succession. We have work to do to reconcile our relationship to wildfire. It’s we who need to adapt, and, through research and restoration, bring back more of the natural diversity and resilience of our forests. Fire will have to have a role in that process, and in understanding that role, Cascade Head and its biosphere reserve can continue to be a laboratory and model.

###

Bruce A. Byers is an ecologist and consultant who advises NGOs and government agencies around the world on forest management, biodiversity conservation, ecosystem services, and environmental communication.

Related Titles

The View from Cascade Head

Cascade Head, on the Oregon Coast between Lincoln City and Neskowin, has stunning ocean views, abundant recreational opportunities, and a rich history of ecological research...