In early September, historic wildfires spread across the West, devastating land and communities in Oregon. The unprecedented and powerful east winds that blew down from the western Cascades on Labor Day 2020 unleashed the most destructive wildfires in Oregon's recorded history. Compared with the Holiday Farm Fire's colossal destruction in the McKenzie Valley, the H. J. Andrews Experimental Forest was affected lightly only on its southwest edge. Today on the blog, author William Robbins connects his new book, A Place for Inquiry, A Place for Wonder: The Andrews Forest, to the 2020 Oregon wildfires and discusses his admiration and love for the McKenzie Valley.

* * * * * * *

The scenic McKenzie River country has been a special place since my first visit to the valley in 1963. Forever fixed in memory, the valley’s scenic qualities seemed to reflect the beauties of Oregon. The spectacular McKenzie River originates in Clear Lake high in t he Cascade Range, tumbles over Sahalie and Koosah Falls, and then flows downstream, assuming a more leisurely journey when it reaches the small town of McKenzie Bridge. Rafters and kayakers navigate white water rapids in the upper river, while fly-fishers stand hip-deep, casting flies in the slower moving waters in hopes of landing a big rainbow trout. Highway 126, the primary route, passes downriver through small communities from McKenzie Bridge, Rainbow, Blue River, and Nimrod and further on to Vida, Leaburg, and Walterville. When I first witnessed the valley’s splendors, the most fascinating features were the small historic cabins above the town of Vida sandwiched between the highway and the river, offering a quaint and rustic presence to passers-by. Because of their proximity to the highway, the cabins likely existed before the roadway was paved and widened.

he Cascade Range, tumbles over Sahalie and Koosah Falls, and then flows downstream, assuming a more leisurely journey when it reaches the small town of McKenzie Bridge. Rafters and kayakers navigate white water rapids in the upper river, while fly-fishers stand hip-deep, casting flies in the slower moving waters in hopes of landing a big rainbow trout. Highway 126, the primary route, passes downriver through small communities from McKenzie Bridge, Rainbow, Blue River, and Nimrod and further on to Vida, Leaburg, and Walterville. When I first witnessed the valley’s splendors, the most fascinating features were the small historic cabins above the town of Vida sandwiched between the highway and the river, offering a quaint and rustic presence to passers-by. Because of their proximity to the highway, the cabins likely existed before the roadway was paved and widened.

My affinity for the McKenzie Valley began with a fishing outing in the spring of 1964. Turning left before the town of Blue River, I drove along the stream of that name until I crossed a bridge and saw a sign announcing the entrance to the “H. J. Andrews Experimental Forest.” That morning I fished Lookout Creek, a beautiful mountain stream shrouded in old-growth Douglas-fir and thick with an understory of vine maple and sword fern. Employed with the Eastern Lane Forest Protective Association that summer, I worked as a choker-setter, clearing a right-of-way road for the Forest Service near Mt. Hagan, high above the McKenzie River, and not far as the crow flies from the Andrews Forest. Before leaving for fire camp southeast of Cottage Grove where I would be crew fireman at the Mosby Creek Guard Station, I learned the trade of “powder monkey,” setting dynamite charges under stumps to blow them apart. Returning again as crew foreman in 1967, our Mosby Creek crew fought a small fire near Mt. Hagan that sent boulders tumbling onto Highway 126 below (the same sorts of debris, on a much grander scale) littering the highway in the wake of the Holiday Farm Fire of Labor Day 2020. Those early work experiences in the McKenzie Valley preceded by decades the research and writing of A Place for Inquiry, A Place for Wonder: The Andrews Forest—and undoubtedly contributed to the book.

When Oregon State University Press published A Place for Inquiry in early October 2020, the book’s release followed the ravages of the Holiday Farm Fire, a conflagration that desiccated some twenty miles of landscape along Highway 126, destroying 431 homes and numerous commercial and outbuildings. At this writing, the fire has burned 173,000 acres and is still smoldering. The McKenzie inferno was only one of several catastrophic fires in Oregon’s western Cascades, triggered when powerful fifty to seventy mile-per-hour east winds blowing westward down the slopes of the Cascades turned small blazes into huge fires and ignited new ones on the night of September 7, 2020. By the time the east winds lessened, and rain fell on the Cascades, the fires had torched more than a million acres in Oregon. The Holiday Farm Fire threatened the lower, western portion of the 15,800-acre Andrews Forest research features and several historical experimental watersheds and its headquarters facility along Lookout Creek. The fire scorched spottily through Watershed 9 and Watershed 1, damaging gaging stations at the mouth of both drainages. The fire also burned lightly into Watershed 2, an experimental drainage of old-growth that was left pristine as a comparator to watersheds that had been harvested in the early 1960s.

At this writing, the headquarters location is safe, the remaining embers dying as the fall rains descend. Because A Place for Inquiry was released while the mega-fire was still burning, is ironic. Scientists associated with the Andrews Forest's 70-year history, have focused numerous investigations on disturbances, both natural and human. As such, the Holiday Fire will provide fertile ground for research. This book demonstrates that Andrews scientists have always pursued disturbance-related inquiries far afield, including studies of the eruption of Mount Saint Helens in 1980, the Three Sisters Wilderness, national parks, and other experimental forests in Oregon. Andrews scientists have also witnessed disturbance regimes in far-away places—Japan, Chile, Germany, and elsewhere, encounters that have provided them with a global perspective.

Because most scientists agree that trends associated with climate change triggered the gale force winds on Labor Day 2020, A Place for Inquiry places special focus on research associated with global warming. Andrews scientists began tackling climate change in the 1980s, addressing the “greenhouse effect,” the consequences of atmospheric gases trapping heat radiating from the Earth’s surface. Writing for Northwest Environmental Journal in 1990, David Perry of OSU’s Department of Forest Science, observed that greenhouse gases and warming temperatures would affect plants because of the longer growing seasons. Natural disturbances, insect and disease infestations, wildfires, and dramatic swings in precipitation would increase. Fred Swanson and many others suggested that warming climates would affect watershed health, and indirectly, forest management. The Corvallis office of the Environmental Protection Agency reported in 1992 that rising temperatures threatened Northwest forests, its woodlands changing from one vegetation type to another, and that fire, wind, pest, and pathogen outbreaks would increase.

When the National Science Foundation funded its initial Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) sites in 1980 (the Andrews was among the first six), the agency did not envision that its researchers would contribute to understanding threats posed by rising global temperatures. The Andrews Forest and other LTER sites, however, became increasingly involved in wide-ranging studies related to climate change. By the second decade of this century, Andrews scientists were publishing articles underscoring the consequences of the warming climate.

Earlier spring seasons, warmer and drier summers, and autumn-like weather extending into October have already had dire implications—increases in the frequency of wildfires, their size, and the severity of the damage they cause. The Andrews Forest’s multiple long-term data sets provide valuable historic information on air temperature, precipitation (rain and snow), soil temperatures (in old and young forests)—some of the measurements dating to the 1950s. Those historic measurements will enable scientists to better evaluate far-reaching changes in climate. Andrews personnel and agency personnel were interested in the effects of warming temperatures on forests and streams and the socioeconomic consequences for citizens living downstream. In the last decade, declining snowpacks, earlier spring seasons, and autumns extending through October were affecting residents in the Willamette Valley through reduced water storage in reservoirs for irrigation and recreation.

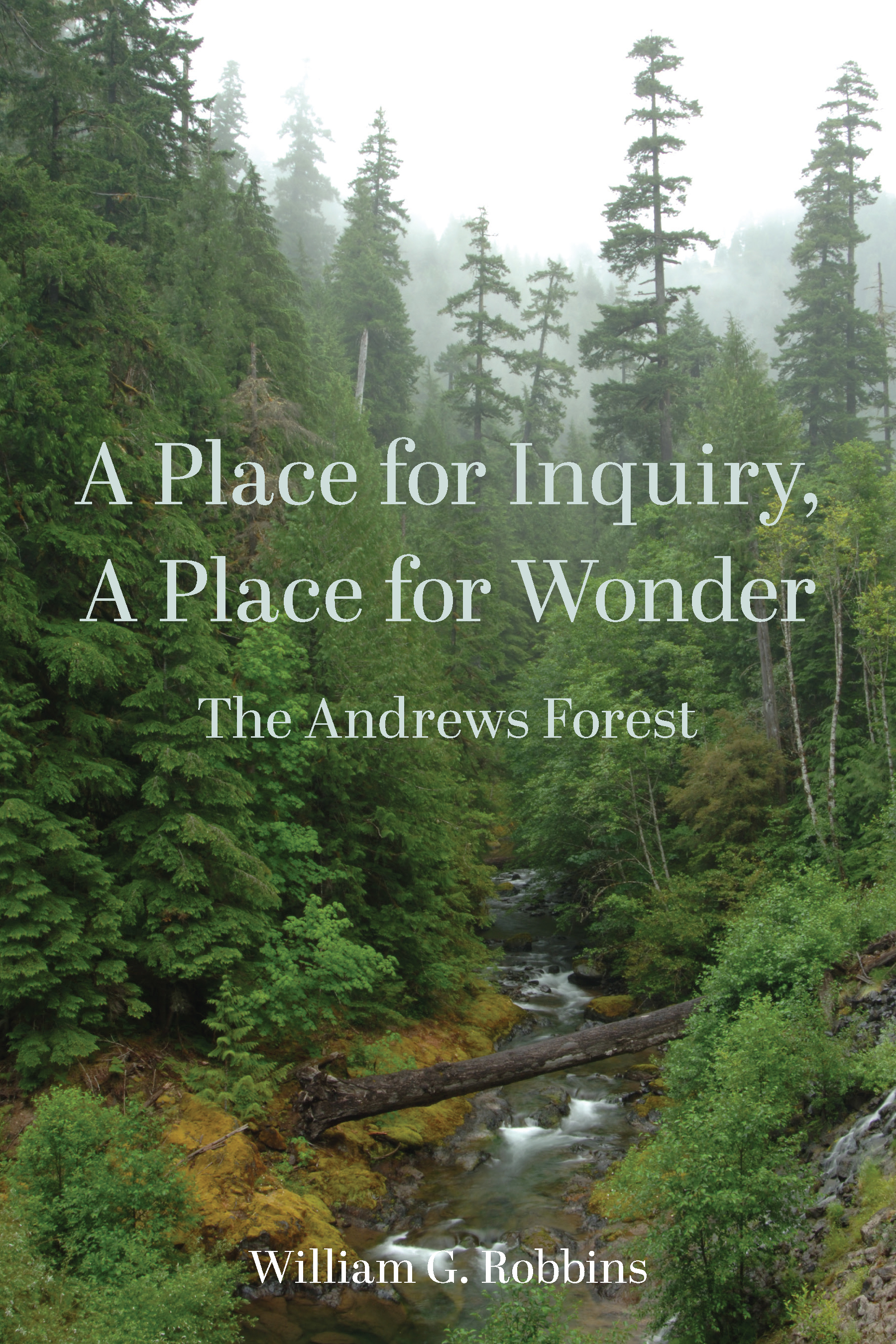

The Andrews Forest website describes the Lookout drainage as “a center for forest and stream ecosystem research in the Pacific Northwest.” It is that and much more. It is a place of more than one hundred bird species, numerous reptiles, and amphibians, and mammals large and small, all inhabiting a landscape shrouded in seasonal fog, rain, or snow (depending on elevation), old-growth trees still covering 40 percent of its 15,800 acres. Beginning early in this century, the forest has benefitted from the participation of humanities scholars in its efforts to cope with a troubled future.

Michael Nelson, who became the lead principal investigator for the Andrews Forest’s Long-Term Ecological Research program in 2012, was the first non-scientist to hold the position. With a master’s degree from Michigan State and a Ph.D. from Lancaster University in England (both in philosophy), Nelson has posed important questions about the social significance of scientific research, viewing the Andrews as “a place of inquiry and research” where scientists investigate the consequences of climate change in a setting that enables them to move beyond old models in anticipating the future.

A Place for Inquiry, A Place for Wonder, a dramatic new research venture for the author, provides the story of the Andrews and what it can offer for the future.

William G. Robbins, a native of Connecticut, served four years in the US Navy before attending college. He holds graduate degrees in history from the University of Oregon and taught at Oregon State University from 1971 to 2002. He retired as Emeritus Distinguished Professor of History. He has authored and edited many books, including A Man for all Seasons: Monroe Sweetland and the Liberal Paradox (OSU Press, 2015).

Related Titles

A Place for Inquiry, A Place for Wonder

The H. J. Andrews Experimental Forest is a slice of classic Oregon. Due east of Eugene in the Cascade Mountains, its 15,800 acres encompass the...