Culture and communication are inextricably linked. Whether it is building a narrative for

ourselves, talking within our communities, or trying to speak across boundaries – ultimately,

much of our cultural practices and how we understand each other are shaped by the stories we

tell. OSU Press author Lisa King explores the efforts and effects of

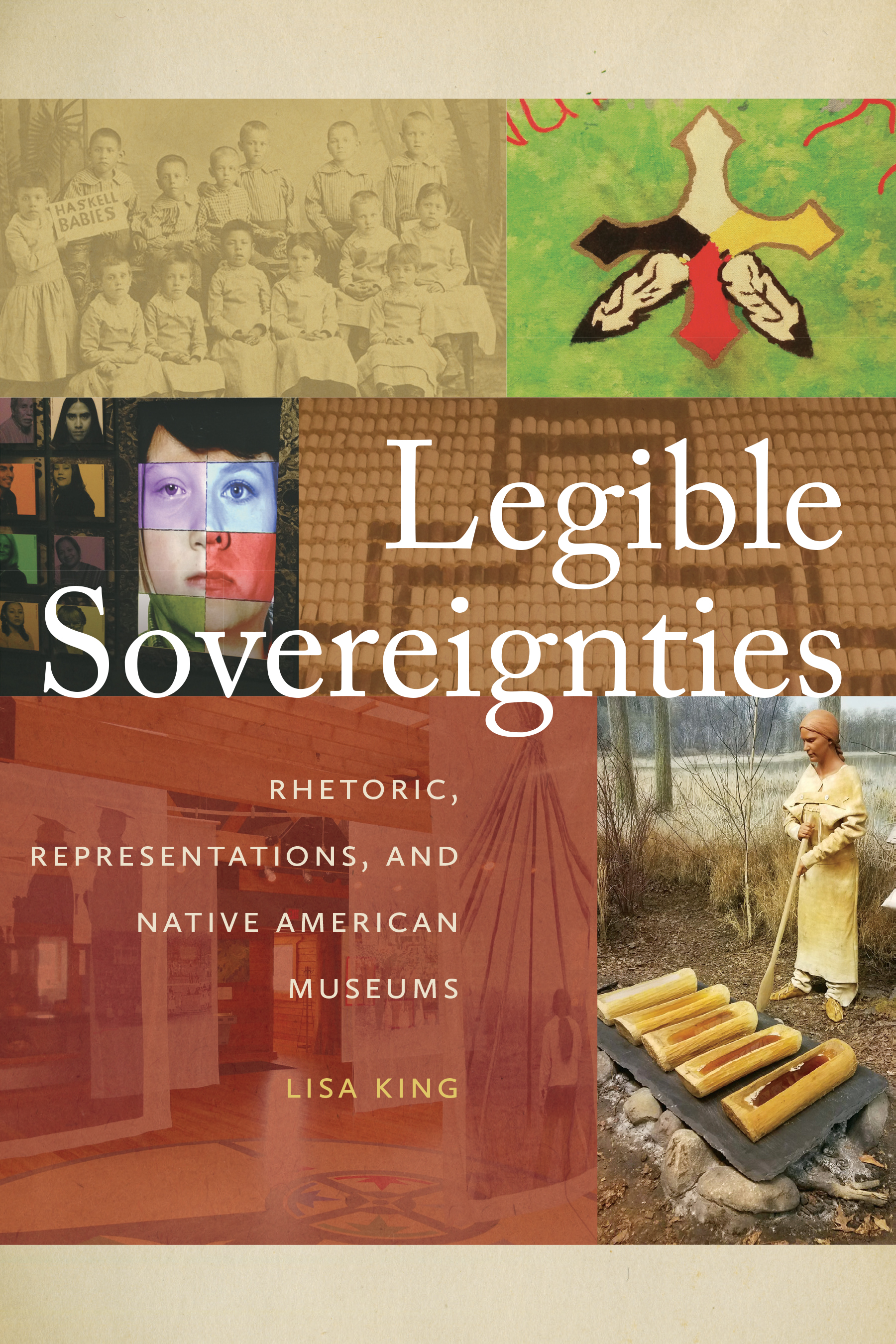

Indigenously-driven stories within Native American museums in her new book Legible Sovereignties: Rhetoric, Representations, and Native American Museums. Her journey to publishing this book began more than a decade ago with her first acquaintance with the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. She explores this awe-inspiring experience that gave her a new perspective into visual rhetoric, museum studies, and public engagement with Indigenous voices.

_______________

My first time to the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in Washington, D.C., was a revelation in many ways. The proverbial dust had settled from its triumphant opening months before, and while I couldn’t afford to be there for the opening ceremonies (grad student budget), I had finally made my way there. The curving sand-colored Kasota stone architecture, the high-domed atrium, the recently installed medicinal gardens: the entire orientation of the museum was unlike anything else on the National Mall, and an emphatic statement of Indigenous presence next to the Capitol building. “We are still here” was the undeniable claim. I was elated.

My first time to the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in Washington, D.C., was a revelation in many ways. The proverbial dust had settled from its triumphant opening months before, and while I couldn’t afford to be there for the opening ceremonies (grad student budget), I had finally made my way there. The curving sand-colored Kasota stone architecture, the high-domed atrium, the recently installed medicinal gardens: the entire orientation of the museum was unlike anything else on the National Mall, and an emphatic statement of Indigenous presence next to the Capitol building. “We are still here” was the undeniable claim. I was elated.

Inside, the exhibits were beautiful, overwhelming in their stories, and an inversion of typical museum exhibit in the clear influence of self-representation in each Native community’s alcove. The Our Peoples exhibit told in some stark terms what the motivations for colonialism were, and the devastating effects of it for the peoples of North and South America. The Our Universes exhibit revealed many of the ways Native peoples of the Americas structure their worldviews, clearly challenging stereotypes of Native spiritual practice and philosophy. The Our Lives exhibit was my favorite, particularly for the ways it tried to complicate notions of Native identity and what Native peoples do on a daily basis to maintain identity and live as contemporary Indigenous peoples. The museum overall was a powerful, celebratory testament to the presence and survival of North and South America’s Indigenous peoples.

Yet there were emerging problems, too. As someone who frequently negotiates back and forth between disciplines (rhetoric and Native American/Indigenous studies, plus museum studies) as a professional and between worldviews as a person, I worried over whether or not the average museum visitor would get it. Museums are widely believed to be purveyors of “Truth,” and so anything the NMAI did would be high stakes. How much history would the average visitors wandering in from the D.C. Mall know? What would their reactions be? Would visitors treat this narrative of survival and resistance the same way they would a display in an art or science museum, for good or ill? Could they grasp the complicated and nuanced and beautiful range of histories, cultures, and present-day lives represented here? Or would they just come looking for the exotic “Indian” in Plains war bonnet and buckskin? In short, I was not sure at all that the exhibits, lovely as they were, would bear the weight of visitors’ likely historical ignorance and the misperceptions they would likely bring with them.

This moment more than a decade ago was the genesis for Legible Sovereignties: Rhetoric, Representations, and Native American Museums, yet as I’ve traveled and worked with other Indigenous museums and cultural centers, I have seen first hand that every institution faces these questions and that formulating answers involves much more than the experience of one museum, one community, and one audience. For this reason, the book highlights the first decade of work at three distinctive Indigenously-oriented or owned institutions. The Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michigan’s Ziibiwing Center of Anishinabe Culture & Lifeways, for example, is a tribally owned and operated institution that developed out of Saginaw Chippewa community’s need and desire for a place to tell their own histories, repatriate their ancestors, and cultivate living culture for the next generations. Its context is deeply rooted in local communities, but its impact has reached beyond initial expectations and intentions to shape local and regional Anishinabe identities for Indigenous and non-Indigenous audiences. In contrast, the Haskell Indian Nations University’s Cultural Center and Museum provides a different kind of story, one that spans more than a century of history and represents more than 150 tribal nations and communities. The tracing of the university’s narrative from boarding school to educational self-determination is key to understanding Haskell as a place, but the story also continues to shift with its audiences’ needs and contributions. In short, all of these places have similar goals, and yet very different needs and audiences to which they answer.

While we might desire a one-size-fits-all solution to re-educate audiences away from misperceptions founded in a narrative of savagism and civilization, what I hope to show is how every story here is unique, and every story here is connected. I talked with curators and museum staff at all three of these sites about their hopes and intentions, I documented the exhibits in their original state and then again as the spaces evolved at their ten-year anniversaries, and I collected audience responses and reviews for all the semi-permanent exhibits. What it adds up to is a rhetorical web of relationships and stories all aimed at taking apart the notion of a “savage” or “vanished” or “frozen-in-the-past” Indian to educate audiences about Indigenous presents and futures. Yet not all of those efforts played out as intended, some stories took a different turn, and sometimes what was assumed to be perfectly legible, wasn’t. Or what started out clear became muddied. Or what the audiences needed changed. In other words, what constitutes “legible sovereignties” for Indigenous communities has to be rhetorically flexible and responsive to audiences and the moment, and these three sites all embody individual and situation-specific efforts to speak Indigenous presence in a way that resonates for everyone involved.

Every time I am in D.C., or Mt. Pleasant, or Lawrence, I go back to visit these beautiful institutions, and every time I am grateful to them for striving to make Native and Indigenous nations, communities, and individuals visible and break down misconceptions. This book is meant to honor those efforts, and in turn to make them visible so that we can continue to learn how to strengthen communication and education across audiences and across communities. They have taught me much, and I offer this account of their stories to you.