Could California condors once again take to the skies in the Pacific Northwest?

The iconic California condor was once at the brink of extinction; at their nadir only 22 birds remained in captivity. However, conservation efforts have shielded the birds from complete extinction; 234 condors live in the wild, and another 170 survive in captivity.

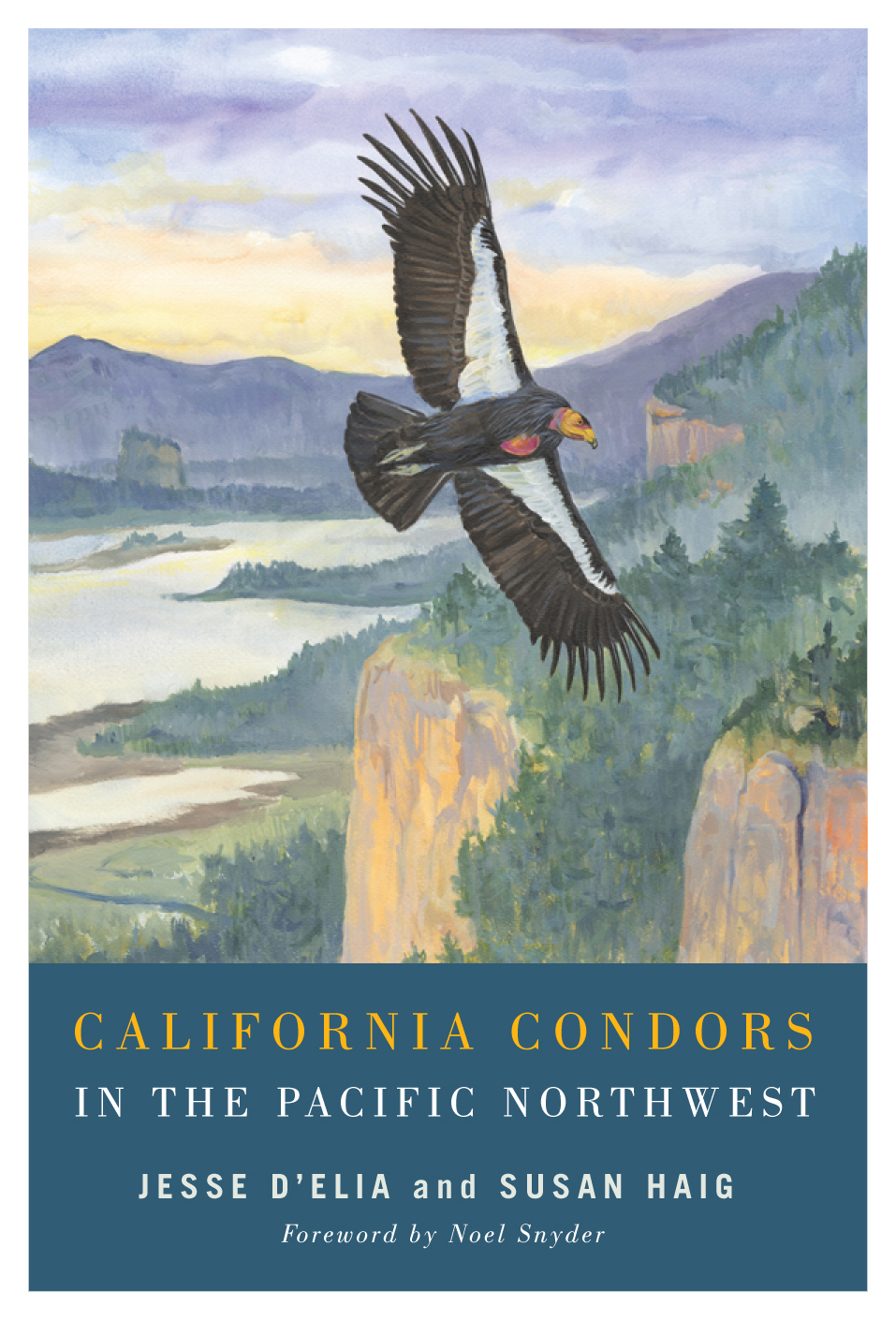

A timely new OSU Press book on condors, out this month, is already generating wide attention. California Condors in the Pacific Northwest by Jesse D'Elia and Susan Haig documents the condor's history in the region and explores the challenges of reintroduction.

Crosscut.com columnist Knute Berger described the book as "an in-depth look at the history of the condor in the territory ranging from the Redwood coast to the Gulf Islands in British Columbia… D’Elia and Haig attempt to lay out a complete record of the condor here, from the fossil records to eyewitness accounts to Native American stories and practices.”

Katy Muldoon of The Oregonian called the book, "a fascinating blend of science, culture and natural history."

Interviews with Susan Haig are available for reading: visit Oregon State University's news release and CNN's Light Years. Haig discusses the challenges of recovery in a Tedx DeExtinction talk: "Bringing Back the Birds of Our Dreams." Jesse D'Elia writes about the book and the implications of its findings on the USFWS Pacific Region blog.

We're pleased today to share Noel Snyder's Foreword to the book.

Foreword

Presently the largest and most astonishing bird in the skies of North America, the California Condor was one of our most highly endangered species by the 1980s, when it persisted only in a region just north of Los Angeles. By the late 1980s it endured only in captivity, but it has since been returned to the wild in selected regions. Fossil evidence from Pleistocene times shows that it inhabited not only California but a continent-wide range stretching from northern Mexico to Florida, New York, and the Pacific Northwest.

The condor was likely a breeding bird in most regions where its fossils have been found, but so far, breeding has been confirmed only in California, Baja California, and Arizona. In Arizona, paleontological research has revealed that the species once nested in caves perforating the many formations of the Grand Canyon and, following releases begun in 1996, it has again returned to nest in these sites. Whether the species ever nested in Oregon and Washington, however, has been a subject of controversy. It was frequently reported seen in this region in the nineteenth century, starting with the epic journey of Lewis and Clark in 1805, but no one has ever documented a contemporary or historic condor nest north of California. This book discusses suggestive evidence that condors were indeed breeders in the Northwest and presents a careful analysis of causes of disappearance of the species from this region by the early twentieth century—efforts that serve as a prelude to a potential program to revive a wild population in the region.

Should a consensus develop that the condor was indeed once a full-time resident and breeder in the Northwest, and should agreement be achieved that the past and present causes of the species’ decline in this region have been reliably identified and countered, it may well prove feasible to reestablish this species as a wild creature in the region. This book goes a long way toward justifying such an effort, although it also thoroughly discusses the information gaps and resistance factors still remaining that could prevent success in such a project.

The last wild condor in the remnant historic population in California was trapped into captivity in 1987, joining twenty-six other condors taken from the wild as eggs or otherwise trapped from the wild. Captives have bred readily, and the total captive population, now maintained in part by the Oregon Zoo, has increased rapidly. Numbers of birds have been sufficient to allow the initiation of release programs to the wild in several locations in California, Baja California, and northwestern Arizona. These release populations, which now collectively include several hundred individuals, have been maintained in part on subsidies of carrion food and have all initiated breeding activities. However, none of these populations has yet attained demographic viability because of a variety of problems, the most important of which has been poisoning stemming from the birds feeding on carcasses of hunter-shot game containing lead ammunition fragments.

California passed legislation outlawing the use of lead ammunition in the condor’s range in 2007, but the poisonings in this state continue because of difficulties in enforcing the legislation and the wide availability of lead ammunition across the country. It seems likely that an effective solution to the lead-poisoning problem may necessitate national legislation that truly removes the sources of lead ammunition and substitutes other equally effective ammunition that is nontoxic. As lead ammunition also contaminates humans to some extent, especially through ingestion of hunter-shot game, such legislation would also be a significant benefit for human health, to say nothing of the benefits to wildlife species other than condors that also suffer from lead poisoning. The insidious sublethal effects of lead contamination on our own species have already led to a banning of lead in paints, gasoline, and plumbing.

Thus, success in reestablishing condors in the Northwest may well depend on success in national efforts to solve the lead contamination problem. But it will also presumably depend on the development of effective solutions to other problems considered in this book. Success in such efforts will surely demand a continued commitment toward conservation of the species by the public and on well-conceived research and management programs to overcome resistance factors.

The re-creation of a viable population of condors in the Northwest would constitute an achievement of substantial importance, not just for those with a special interest in birds, but perhaps especially for the many Native Americans living in the region, whose cultural traditions have always honored this species as a supreme master of the skies.

—Noel Snyder, retired U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist in charge of condor research in the 1980s and lead author of The California Condor: A Saga of Natural History Conservation

—by Brendan Hansen, George P. Griffis Publishing Intern, OSU Press

Related Titles

California Condors in the Pacific Northwest

Despite frequent depiction as a bird of California and the desert southwest, North America’s largest avian scavenger once graced the skies of the Pacific Northwest...