On a warm day in April, when the COVID-19 public health authorities are advising Oregonians to stay home and enjoy the effulgence of spring from “balconies or open windows,” I have been thinking about the poet Hazel Hall (1886–1924), whose life and work are admirably detailed in John Witte’s introduction to OSU Press’s centenary edition of The Collected Poems of Hazel Hall (2020). The Collected Poems is three books in one, thematically linked by the burdens of social isolation and the gifts of profound solitude—Curtains (1921), Walkers (1923), and the posthumous Cry of Time (1928).

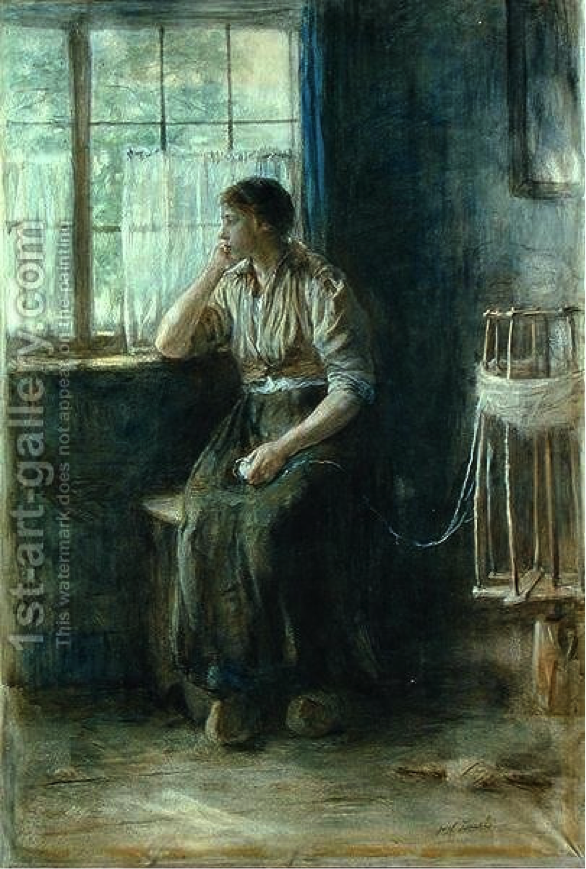

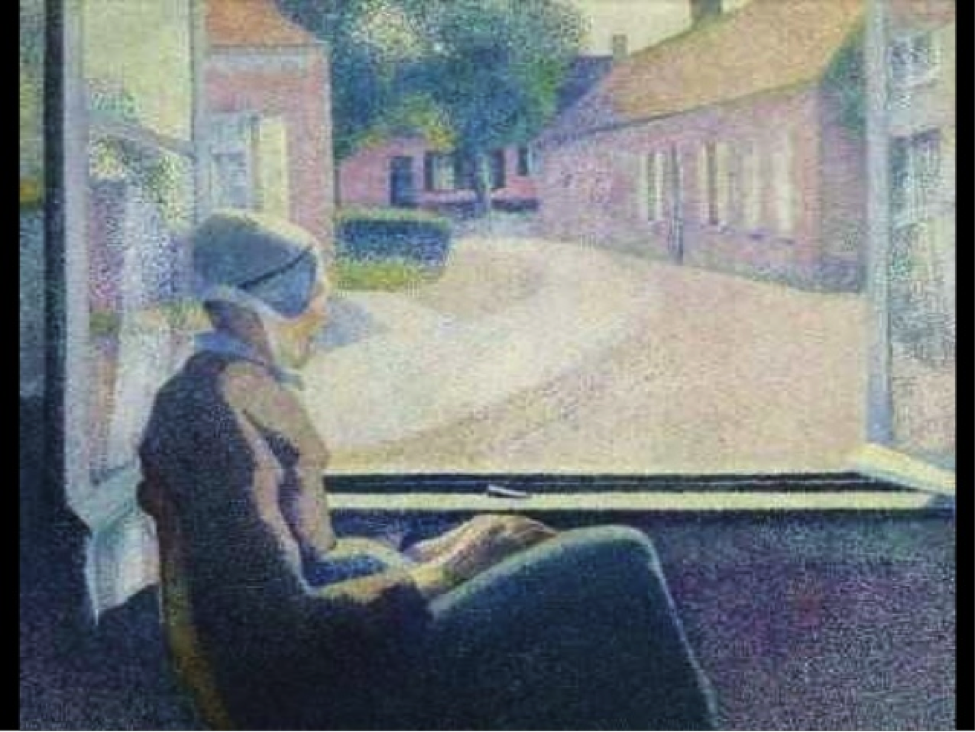

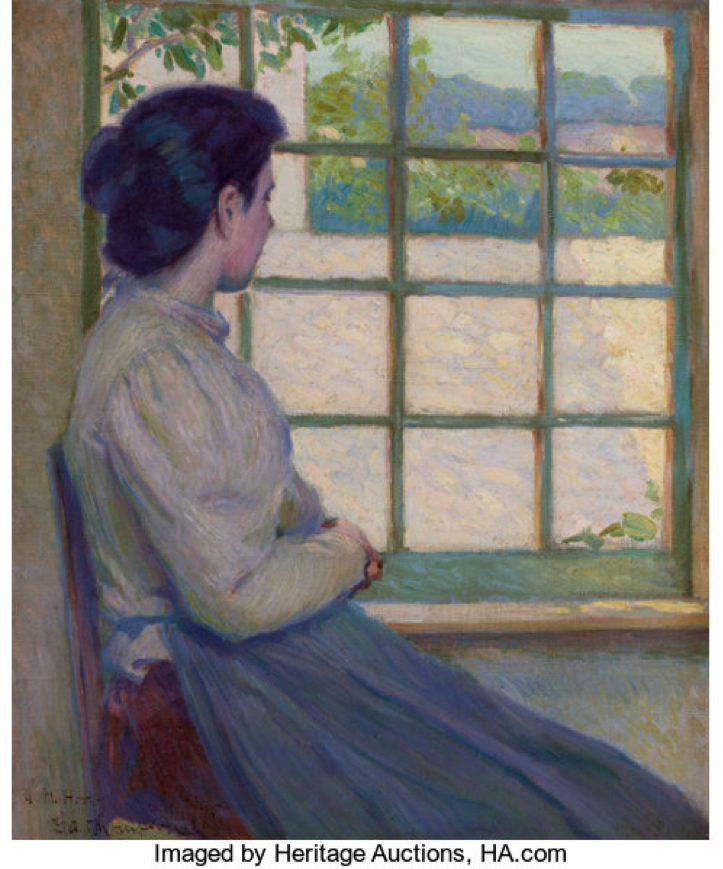

Jozef Israels (Belgium) Georges Serat (France) Carl Vilhelm Holsoe (Denmark)

Woman at the Window Untitled Woman at a Sunny Window

Hall lived a shut-in existence from the turn of the century to her death in 1924, just blocks from my residence in Northwest Portland (the house still stands, marked by a historical plaque). A bustling neighborhood known for well-coiffed Victorian houses, its tree-lined streets are now stunned into sudden quiet, desolate but for the occasional jogger in a face mask.

Hall was not a shut-in poet by choice or public duty. She was confined to a wheelchair following a childhood bout with scarlet fever, limited to viewing the outer world from a second story’s cross-pane windows in her family home. From this narrow space, poems were written and posted to national publications, earning her a lasting literary reputation. To assist with family finances, she took in sewing and needlework; her poems include fascinating details about fashioning often-glamorous fabrics into elaborate garments and embroidered table linens for the wealthy. She propped a mirror on the window sill to expand the limits of vision from her stationary position. Yet it is impossible not to note that Hall was also the casualty of a pandemic. In the pre-antibiotic age, the Bureau of Labor and Commerce Tenth US Census Report notes that scarlet fever outbreaks were especially severe in Western Oregon in the waning years of the nineteenth century: many died. Long-term effects of untreated or inadequately treated scarletina included a range of potential complications, from rheumatoid arthritis to heart conditions. Although exact details of Hall’s illness and lingering disability are scarce, the phenomenon of the “cytokine storm,” a reactive misfiring of the immune system we hear so much about in COVID-19 cases, offers at least a plausible explanation for her fragility. We know—the poems tell us—that she could not move without pain; she enjoyed literary celebrity as a poet for a decade, and died in her thirties.

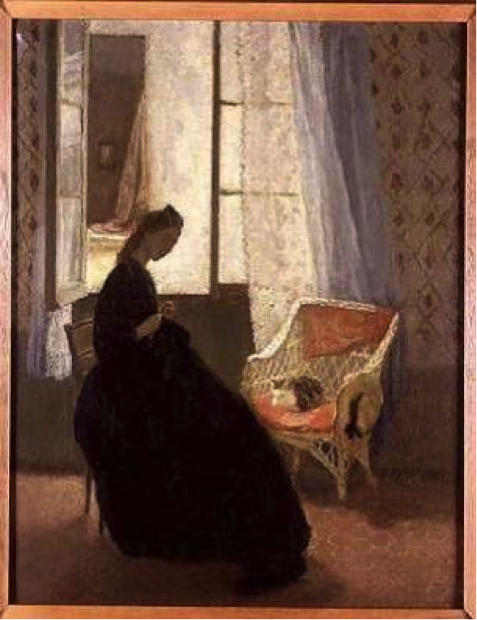

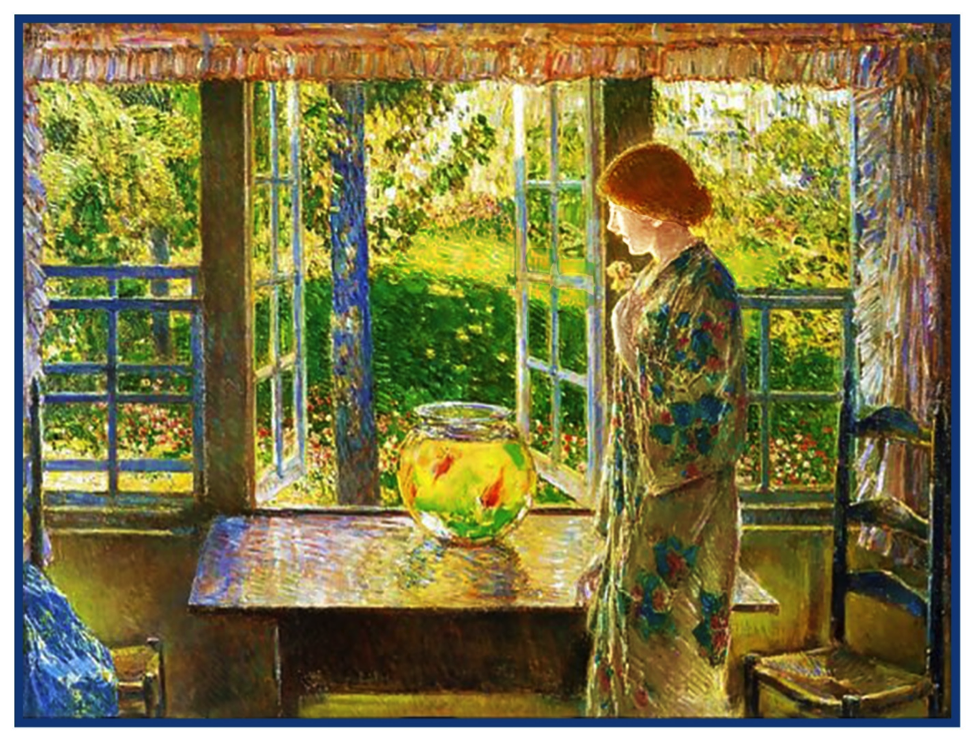

Gwen John (UK) Childe Hassam (US) George Albert Thompson (US)

Woman Sewing By the Window The Goldfish Window Woman by the Window

I find it easy to reach for Hall’s poems now because they evoke the sensations of a life in which the colors and pollens of spring are experienced largely at a distance. These include a keen awareness of space, of visualization, a heightened attentiveness to listening for what lies in the world beyond the scope of a narrow room. Above all, her poems take the measure of the troubled human spirit in imaginative unrest. In some poems, the sense of limited mobility is nearly unbearable; in others it also opens onto soaring transport. Her poems combine scrutiny of the walls, floors, ceilings, and window views, with contemplation of vast unknowns and the passage of time. Many poems achieve their effects by juxtaposing that which is most painful—an impending dread or acceptance of inevitable mortality--with that which is most immediately beautiful—the touch of luxurious fabric, the warmth of the sun on her hand, the flicker of shadows on the wall. In one poem, she describes the sun as her “glamour” (3). Witte’s introduction describes the moments of transport as “oceanic” (xv). Today, the poems seem nearly to collapse the distinction between individual and private illness and our collective isolation, the sensations of cramped-in solitude we are witnessing on a larger scale, while news daily floods the grids of our screens.

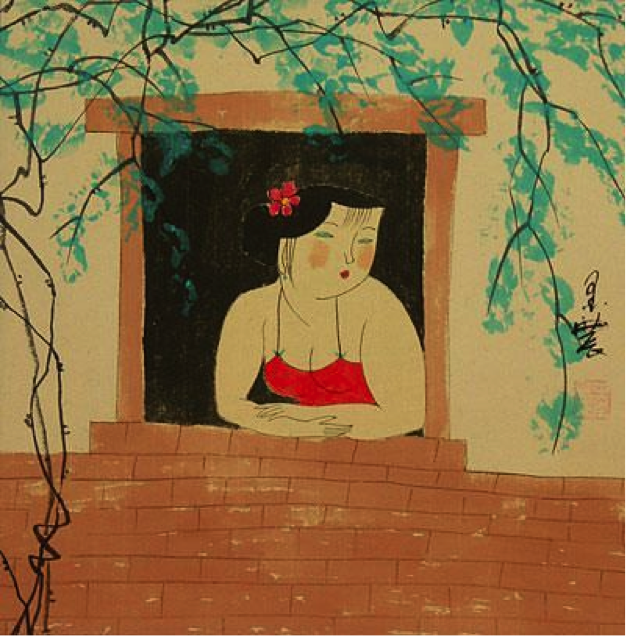

Mo Nong (China) Henri Matisse (France) C.D. Friedrich (Germany)

Chinese Woman by the Window Young Woman by the Window A Woman by the Window

Hall’s poems, while disciplined and detailed, register what we can readily observe in our housebound selves--the mind’s propensity to wander and dig deep when the body is confined. A single Hall poem may travels all seasons within its compass. Window frames organize the movement between things and thoughts, the metaphoric edges of her existence. In “Counterpanes,” the mind travels from the “four grey walls’ grey winds” to a compensatory patchwork of lines on the page that offer gratification in the shape of a poem:

I will patch me a counterpane

For mine is worn with scars

And I fear the iron rain

Of a ceiling’s splashing stars” (14).

“Curtains” juxtaposes the beauty of “filmy seeming” and “chintz of dreaming” with the grim deluge of “what rains utter” (1). And in “Frames,” the narrow space of the window sill marks the threshold of wonderment:

Brown window-sill, you hold my all of skies

And all I know of springing year and fall,

And everything of earth that greets my eyes—

Brown window-sill, how can you hold it all? (2)

The arts of pandemic for our time, I’d like to think, include the tensions between housebound domesticity and the forces that propel the imagination toward outward and inward vistas. In visual art from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the genre paintings of “women by the window” took up the question of emerging women’s voices and represent the force of that longing. I have assembled a compilation of my favorites here.

In the meantime, Hazel Hall’s poems make worthwhile reading now. Her time has come round again, as we settle uneasily before our open windows, and wonder when and how all this will come to an end.

- Anita Helle, Professor of English in the School of Writing, Literature, and Film at Oregon State University